Extended exposure to Can’s music will soften and dislodge any unexamined ideas you have about “songs” and “jams” and “cool music.” Convened during tumult but naturally disciplined, Can foregrounded what felt right, together, in the moment. The band never performed live with a set list, nor did they reproduce any of their recordings on stage. Their recorded catalog is important, in part, because everyone can claim it: punks, beatmakers, ambient buddies, moms, dads, jammertons, spiritual docents, meek commuters, corrupt overlords. In their formative years, Can played as many art happenings as concerts and, by the end of their run, they were logging top ten hits, trying to play reggae, and inviting strangers to sing with the band. As well they should have; this is how they found their first two singers, Malcolm Mooney and Damo Suzuki.

One of the great rhythm bands with as much space as sound in their music, Can are perhaps best thought of as instrumental composers. The four main members rarely sang, and when they did, they generally used other people’s lyrics. The two singers who did write in English had such specific relationships to words that it seems unfair to think of their vocals as narrative, or as even words with specific, denotative meanings. The singers were as subtly and steadily musical as the instrumentalists they played with. (Language doesn’t stand a chance with this band.) Think of Can as making an eternal weave that they cut into human-sized pieces, and you’re close. If you leave yourself open to Can, the Sixties and Seventies fall into place and the division between hippies and punks dissolves.

Can formed in 1968, when student dissent was exploding across Europe. Co-founder Irmin Schmidt has made it clear that the band was not political in origin, though. As he told author Rob Young, in All Gates Open, “We were not involved in the ’68 movement, physically or even theoretically. In forming a group at that time we were not starting a commune; it was professional musicians who gave up part of their career, and gave up, above all, the idea of authorship. We were a collective, and inventing collectively.”

This mission was partly a response and a nod to Karlheinz Stockhausen, who both Schmidt and bassist Holger Czukay studied with. (Later in the band’s history, Stockhausen wrote a note to the immigration department of Cologne on behalf of singer Damo Suzuki, who’d been arrested on an old vagrancy warrant: “Society dearly needs birds like these.”) As much as Schmidt and Czukay admired the composer, they were anxious to get away from the idea of a towering, creative monad. As Czukay said of Stockhausen, “He was the church in the village. Everything, all the houses, were built around this church.” In 1966, Schmidt went to New York for a conducting competition and ended up hanging out with Terry Riley, La Monte Young, and Steve Reich. “Reich gave me It’s Gonna Rain on tape,” Schmidt told me. “This was the first time I heard this technique of the tape loop, and it totally fascinated me.”

In the fall of 1967, Schmidt invited Czukay to come back to Cologne and form a group. Groups like AMM and Musica Elettronica Viva were early models. “Rzewski had formed [MEV], which very spontaneously created music and they had not one composer,” Schmidt told me in August of 2022. “The music was the music of the group, and that was one of the influences for me to found Can. The main thing was that the music happened spontaneously between four, five, six people.”

Czukay was teaching in Switzerland and when he arrived in Cologne, he brought one of his students, a young guitarist named Michael Karoli. Popular music did not seem nearly radical enough to Schmidt and Czukay, but Karoli played them some Beatles tracks and a détente was reached. As Schmidt told David Stubbs, he wanted to have “a brilliant jazz musician and a classical musician and a rock guitarist – three phenomena of the twentieth century – and bring them together, see what happens when these persons meet, see what happens when these people, with all their abilities, start from scratch.”

Can was a product of dialectical churning—the happy grind between the composer and the group, the free and the regular, the abrasive and the sweet, the Bluto and the Popeye. Drummer Jaki Liebezeit had been playing improvised music for years before Schmidt asked him for names of drummers who might join their band. Tired of playing free jazz with Manfred Schoof’s band, Liebezeit nominated himself. Schmidt was surprised but trusted Liebezeit, having little idea that he was starting a band with a clock-like dynamo who relished straight time and knew there was eternal change inside regularity. (Somewhat unexpectedly, Karoli said that Liebezeit gave him “the creeps.” “I thought he was a murderer, or someone capable of committing a murder,” David Stubbs reports Karoli saying, in Future Days.) The band initially included a composer and flutist named David C. Johnson, another member of the Stockhausen orbit who did electronic work at the WDR studio in Cologne. After a few film soundtracking moments and live shows, Johnson took off and was replaced by the band’s first singer, Malcolm Mooney, an American painting student trying to avoid the draft while bouncing around Europe with a friend. Hildegard Schmidt, Irmin’s wife (and the band’s manager since 1972) invited him to meet Irmin. (Fun fact: West Germany officially forbade managers for artists. As Stubbs reports, “such business was supposed to be handled by the art agency of the Federal Employment Office.”)

“When Malcolm came into the studio, we were working,” Schmidt told me. “We had ‘Father Cannot Yell,’ the instrumental version, sort of done. We were very happy about it, we played it to him, and he spontaneously sang. He was not supposed to become a singer. He was a friend, a painter, but when we put the tape on, he made up words on the spot. We found that it made the piece better. It was wonderful. So from that moment on, he was the singer.”

The liner notes of the The Lost Tapes reproduce Czukay’s recollection of the same moment: “We recorded the first piece—‘Father Cannot Yell’—and I said to myself, ‘Holger, would you have ever expected that you would play something like that?’ I was surprised by myself, I couldn’t believe it. Because I was thinking in completely different terms; I thought we were making a group like Stockhausen. And then Malcolm came in and we think, ‘Why not Stockhausen with a hell of a drive?’ This was not experienced before!”

Can had been a band for less than a year when they started recording in the first iteration of Inner Space, fashioned quickly in one room of a mansion outside Cologne called Schloss Nörvenich. An art collector named Christoph Vohwinkel rented the building to give artists space and let Can (also called Inner Space at the time, confusingly) stay and work for a year rent-free. Schmidt was playing organ and early synths, Czukay was on bass, and Karoli was on electric guitar. Many of the band’s early recordings were done for goofy and horny experimental short films, though some tracks were just pulled from the marathon sessions that became the band’s default working method. Mooney was an instant dab hand and the band’s first recordings, later released as Delay 1968, plant a stake right in the middle of it all. They sound a bit like Hendrix, a bit like the Who, maybe the Velvets, but mostly like Can, a band that has the distinct feature of listening to itself and having patience with the unfolding of things, an attitude they could have learned through free jazz improvisation or the compositional ambitions of the post-serialists. Mooney was a great presence, and still sounds perfect on these early records, but he had fights inside himself, bigger than music. After a year or so, he left and was replaced by Kenji “Damo” Suzuki, a young Japanese man Czukay and Liebezeit heard singing in the street.

Suzuki’s voice is as unpredictable as any instrument and as piercing as any electronic sound source. What the band was able to achieve with Suzuki was an ability to never decide. He looked great in a velvet one piece jumpsuit and made English stranger than silence. They loved repetition enough to sound like a rock band, but they rarely wrote the hooks or stories a hit demands. (They could, though—see “I Want More” and “Vitamin C.”) And none of the instrumentalists in the band much thought about what other people did in their roles. Czukay kept great time on the bass but often provided whatever served as the melody. Karoli had been influenced in Cologne by Michael Birl, a cellist who played the strings with a vibrator, and that sensibility stuck with Karoli; sounds and shapes were more important than traditional guitar parts, although he played those, too. Schmidt is such a subtle band member that it’s often impossible to remember what he did on a particular track but every time you do hear him, you realize the song would be radically different without his part. In the center of it all was Jaki Liebzeit, subtly altering the intensity of stick hits and demoting cymbals to near banishment. (He was OK with the hi-hat but the crash and ride got intermittent love at best. As he told Stubbs, cymbals are “white noise.”) Listen to Liebezeit on a track like “Mother Sky” and you’ll hear how patterns and melodies and forms are not the only way to convey musical information. Traditional concepts of writing are besides the point. There is so much spiritual and psychic energy in Liebezeit’s drums that you could never live long enough to wear it out. Michael Rother of Neu! and Harmonia made four albums with Liebezeit, as many as he made with either of his bands. “Jaki was a magician,” Rother told me.

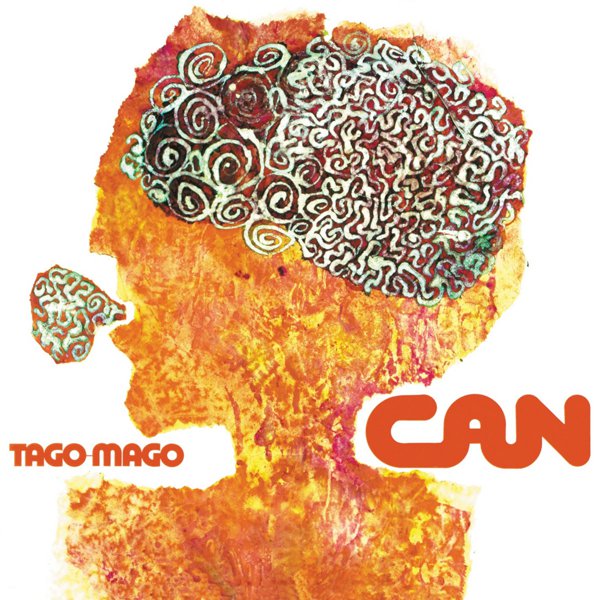

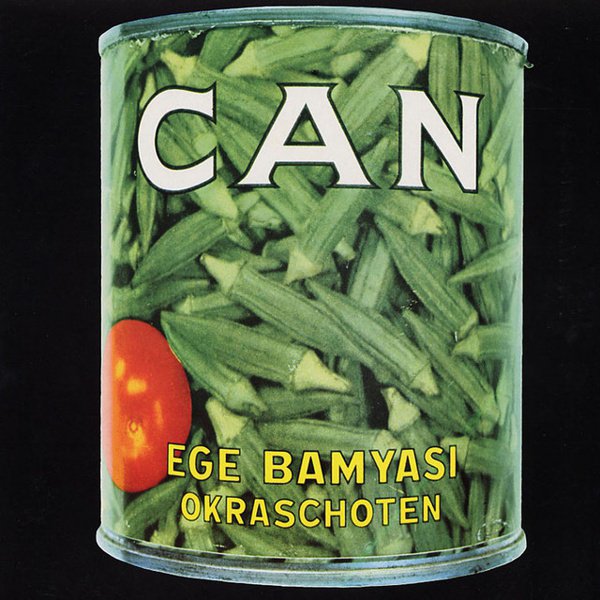

Through the 1973 album, Future Days, Suzuki and Can made a version of rock music that had no real holding container. Songs could go on for twenty minutes or two. The catchy ones weren’t the shorter ones. The band didn’t use a traditional recording studio for almost five years, and then only for mixing. The records now thought of as stone classics, like Tago Mago and Ege Bamyasi, were recorded to two-track in converted spaces never imagined as recording studios. In 1971, the band moved from the Nörvenich mansion and took over an abandoned cinema in Weilerswist near Cologne. “These were eight years spent in this room,” Schmidt said about Weilersist to Young. “Our normal life when we were here, we started working at two, three o’clock here, sometimes four o’clock, and then went away when other people went to work, at six o’clock in the morning. And we did that day after day, all year long, without any interruption, except to tour.”

A lot of what they did was cut down what they had recorded, and much of that work fell to Czukay. As Stubbs reports Schmidt saying, “Holger edited. He was the technician. But the editing was shared by the rest of us. The decision-making as to how the collage was constructed was down to Michael, Holger and me. Jaki didn’t like the editing thing at all – but he had a very important role. He listened to it and if we had fucked up the groove it was not allowed. We had to, when we made edits, make sure there was a continuity of the groove. It could change, but it had to make sense as a groove. It couldn’t speed up for no reason, for instance. The architecture was done all together.”

When Suzuki left, the band ended up with a fitful relationship to vocals. Czukay sometimes did his comic thing; sometimes Karoli did his goth schtick. The band eventually welcomed in two members of Traffic: Rosko Gee on bass, and percussionist Reebop. Albums like Saw Delight have aged better than the band’s early psych freakouts. Long a band with its mind and ears all over the world—a condition Julian Cope calls, very suspiciously, “internationalized”—Can started playing a nameless hybrid of various musics in the mid Seventies. Sometimes like reggae, sometimes like variants of Turkish rock, late Can albums are likely going to be the biggest revelation for a newcomer now. My money is on a big Flow Motion revival any second. Mooney returned to the band briefly in the Eighties for Rite Time (it was not) and now he is playing live with a band that includes several Can numbers in his set, as is Suzuki. My favorite quote about Can came from Karoli, quoted in the Stubbs book: “The soul of the entire thing was not composed of our four or five souls but was a creature named Can. That is very important. And this creature, Can, made the music. When my hour comes, I’ll know that, apart from my children, I’ve helped create another living being.”