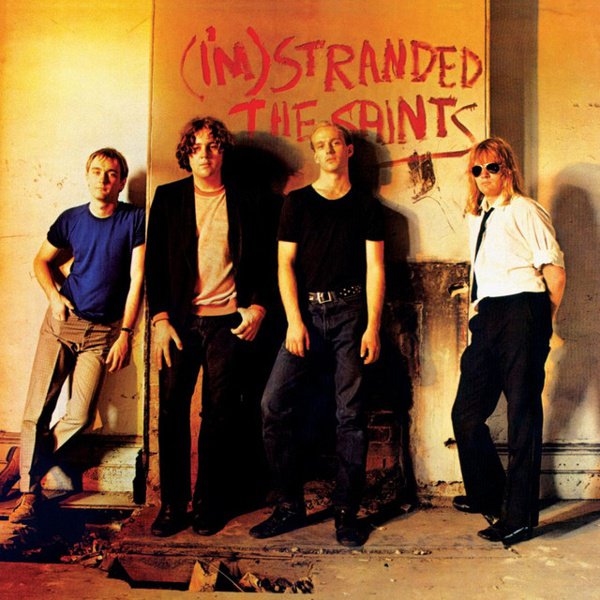

If Ed Kuepper is known for anything, it’s for the three years from 1976 to 1978, where his first band, The Saints, off-handedly defined and then rejected an entire genre of music, while influencing an entire generation of musicians. The story’s well-known: self-releasing their debut single “(I’m) Stranded” in 1976, the key Saints line-up — Kuepper (guitar), the late, great Chris Bailey (voice), Kym Bradshaw (bass), and Ivor Hay (drums) — found themselves hailed as progenitors of punk, after rave reviews in the UK music press caught both the band and the Australian culture industry by surprise. Moving to London after recording their first album, (I’m) Stranded, The Saints had a top forty hit with “This Perfect Day”, before falling out of favour with the UK music scene for not sticking to the punk script – they had long hair, after all, and their music was way too creatively voracious for punk to contain.

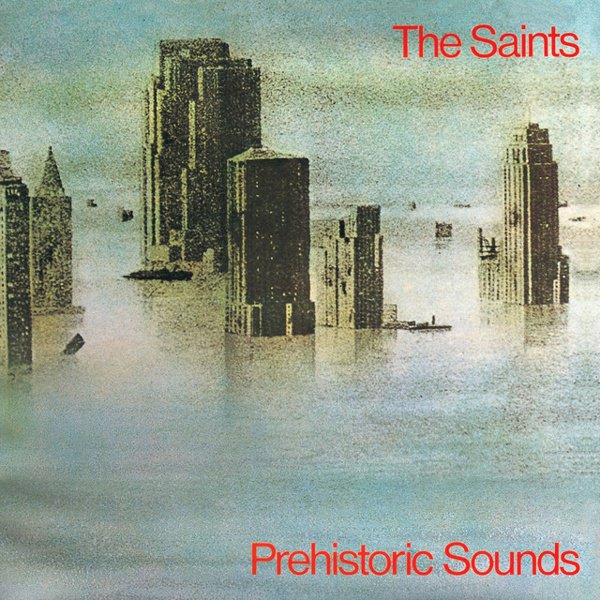

By their third album, Prehistoric Sounds, The Saints had transformed their sound from buzzsaw garage rock to a mutant R&B/soul/garage hybrid. But there was inter-personal friction between Bailey and Kuepper, which led to the group’s split in late 1978. Bailey would continue with the Saints’ name, releasing some great EPs and albums – check Paralytic Tonight Dublin Tomorrow and The Monkey Puzzle, for starters – but it never quite felt the same without Kuepper, who subsequently returned to Australia and, for a time, thought he was done with the music industry. The legacy of that first Saints line-up, though, is undeniable – they pretty much kick-started the DIY, punk rock ethos in Australia; outsiders and antisocial misfits were emboldened by seeing that first line-up live, with Nick Cave recently recalling, “It is impossible to exaggerate the resulting galvanising effect on the Melbourne scene… the Saints were Australia’s greatest band.” And “(I’m) Stranded” and “Know Your Product” are widely accepted as canonical texts of Australian music.

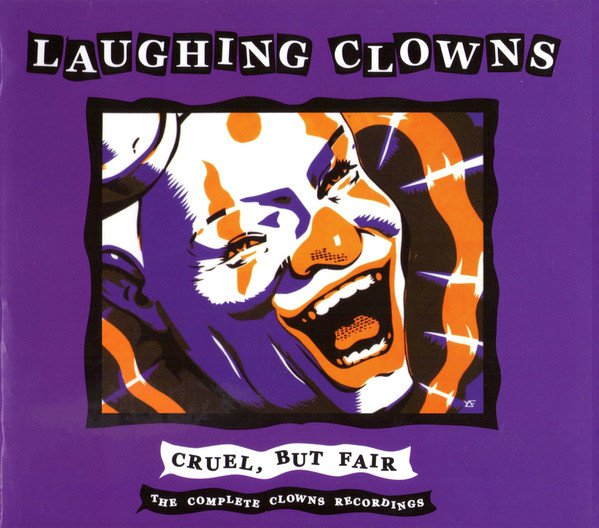

But some of Kuepper’s best work has been done after, and outside of, the legacy of The Saints. Indeed, soon after that group split, Kuepper formed a new group, Laughing Clowns – named after the titular song that would have been the next Saints single, had the Kuepper-Bailey line-up stayed together – and went on to release some truly staggering music. While in some ways an extension of the approach The Saints took with Prehistoric Sounds, with piano and brass a constant presence in the group, the Laughing Clowns’ music went way further, with Kuepper drawing from the free jazz he’d heard in London – Archie Shepp, Pharoah Sanders, Albert Ayler – and building improvisation into the increasingly capacious songs he was writing.

They were never really post-punk, and they most certainly were not punk-jazz or jazz-punk – leave that to the James Chances of this world – indeed, if anything, they extended a mood, and an ethos, that stretches through an alternate musical history, from the songs of Brecht and Weill to the unpredictable hypnotism of Can at their best, via Carla Bley’s compositions for the Jazz Composer’s Orchestra. Part of the magic of Laughing Clowns was the line-up – with players like Jeffrey Wegener on drums, Louise Elliott on saxophone, and Les Millar on upright bass, Kuepper was surrounded by sensational musicians who played with an exploratory sensibility that suited Kuepper’s expanded horizons.

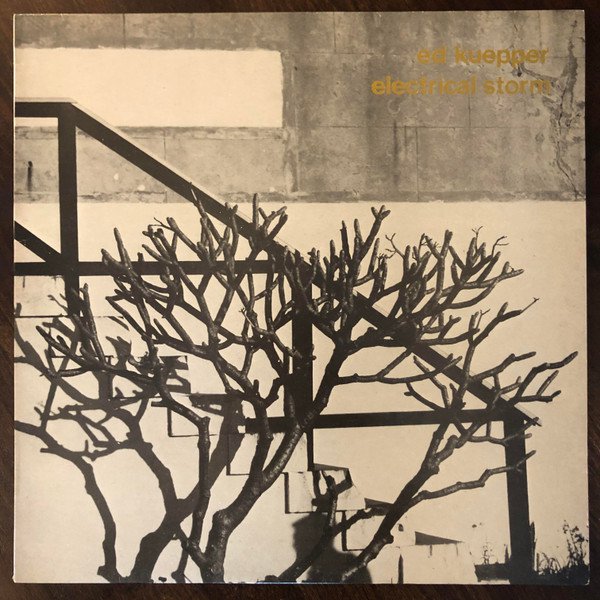

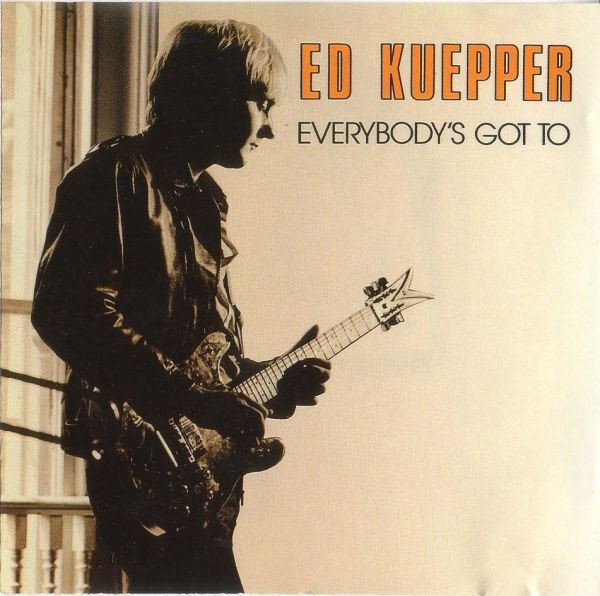

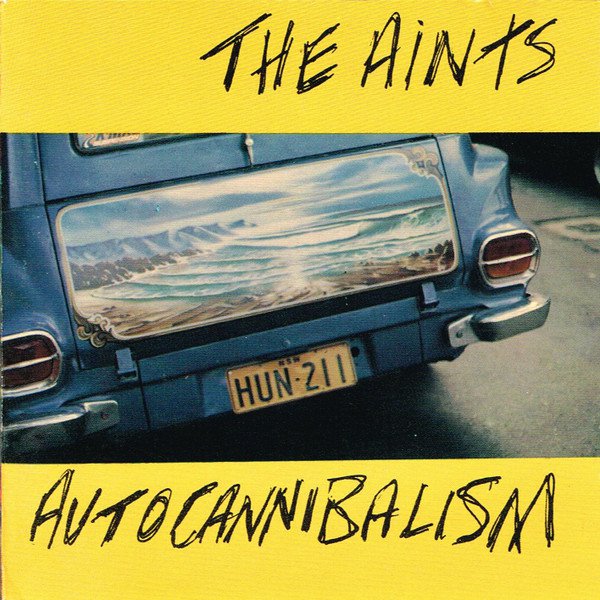

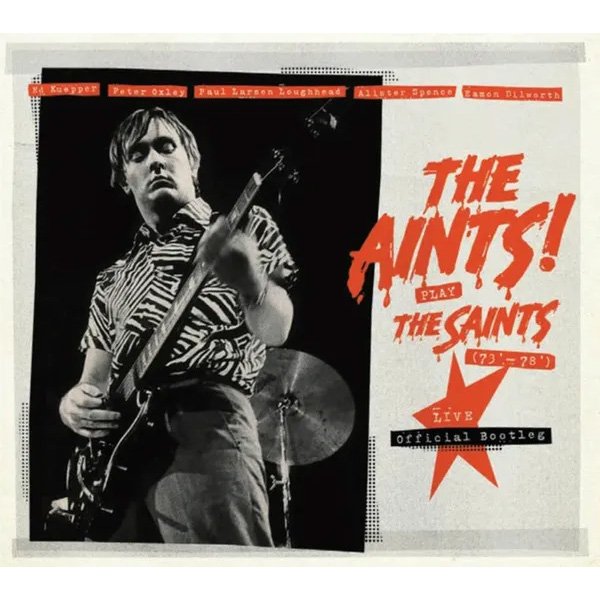

Laughing Clowns disbanded in 1985 – after, notably, Kuepper had also done a brief stint as a touring musician with Bailey’s Saints, though this time on bass – after releasing three albums, and a clutch of great singles and EPs, all later compiled on a three-disc collection, Cruel But Fair. Kuepper subsequently launched a lengthy and at times tempestuous solo career, beginning with 1985’s pared-back Electrical Storm. At his most productive, Kuepper felt like an elemental force – see the early nineties, where he produced a good eight albums in quick succession, five solo and three with his third group, The Aints, whose fearsome volume and intensity reconnected Kuepper with the spirit of those early Saints performances.

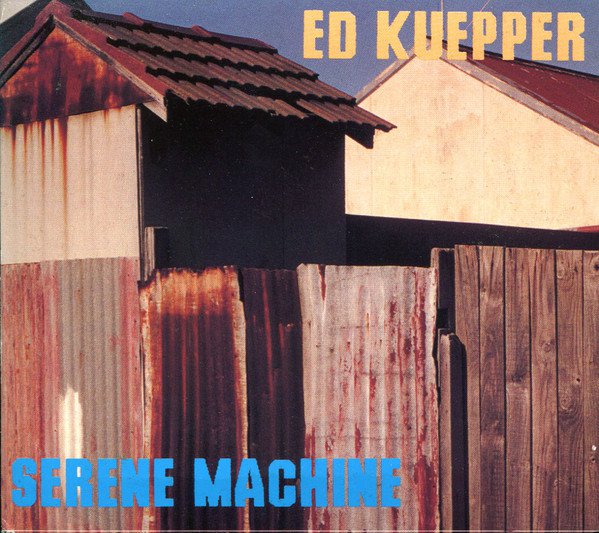

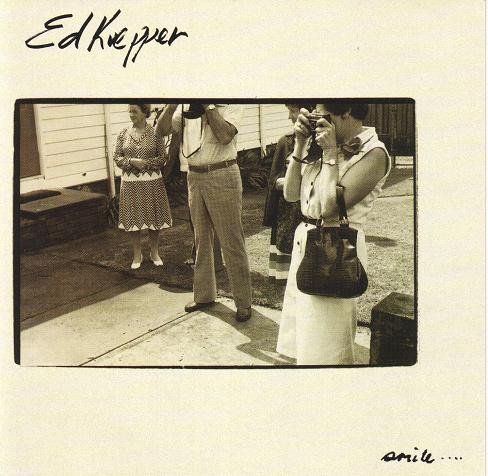

Kuepper’s solo music of this time tended towards acoustic, reflective material, with the occasional pop gem (“La Di Doh”, “Real Wild Life”) in amongst a body of work that touched on plenty of different genres – there’s an overarching interest in blues and folk forms, but you can still hear elements of the garage simplicity of The Saints, the eloquent freedoms of Laughing Clowns, plus dalliances with electronica and sampling culture, the latter best heard on songs like the “Fireman Joe” from 1996’s Frontierland, which Kuepper once quipped was his ‘psychedelic pop’ album.

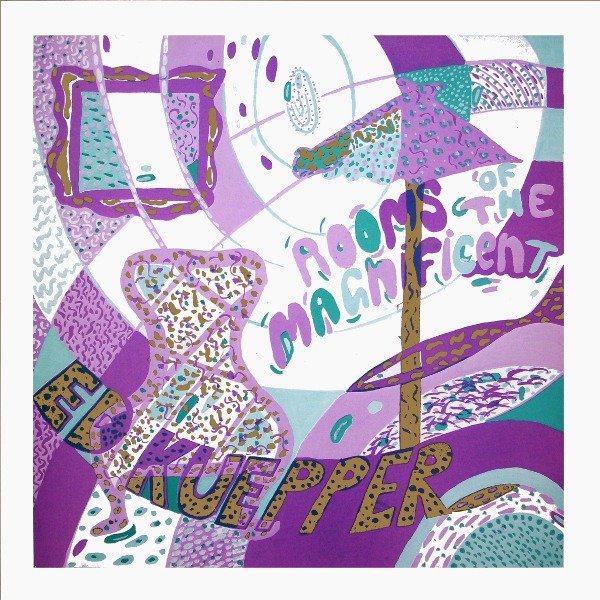

But after releasing a clutch of more curious albums across the nineties – for example, the instrumental mood palettes that are dotted throughout The Blue House, or an unofficial series of mail order-only albums, like I Was A Mail Order Bridegroom and Exotic Mail Order Moods, where Kuepper would often ransack earlier material for reconfiguration – Kuepper’s solo output slowed significantly. This was partly due to other commitments, whether the reformed Laughing Clowns, a series of brief resurrections of the Kuepper-Bailey line-up of The Saints, or two stints as a touring guitarist with Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds (in 2009 and 2013). The reformation of The Aints in 2017 had Kuepper reclaiming and grappling anew with the material from that original Saints line-up – there’s a sense, here, of setting the record straight, and breathing new life into Kuepper’s history.

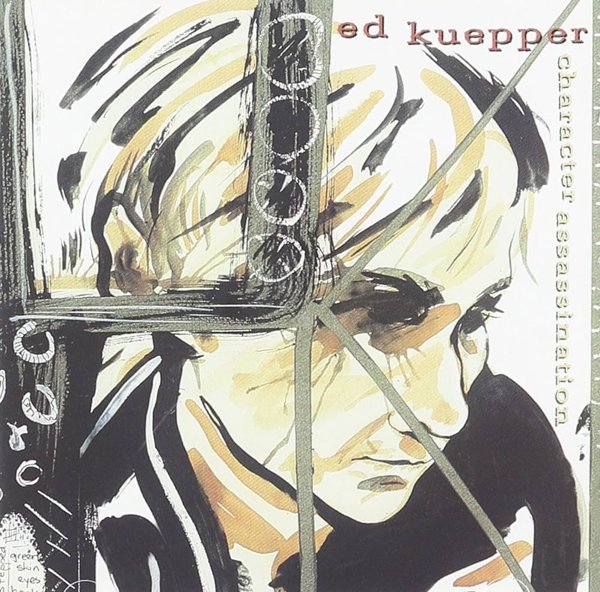

For this writer, Kuepper has always been a standard-bearer for Australian music, without ever aligning to some daft, misguidedly jingoistic idea of what ‘Australian music’ could, or should, be. He’s a heavy presence in our culture – sardonic, droll, wise, endlessly creative, continually inspired, genuinely unpredictable. His guitar playing is every bit as idiosyncratic, and jaw-droppingly inventive, as his songwriting and his singing: indeed, he’s never quite got his due as a face-melting noise guitarist. And he’s one of a very small number of musicians from his generation whose new music excites me, or who I’d still go to see live in new contexts, such as his current touring duo with The Dirty Three’s Jim White. There’s no one doing it better, nor with such style and eloquence. All hail the self-proclaimed ‘king of rock’n’roll’.