There are many kinds of Japanese independent music – as in many other parts of the world, ‘independent music’ first meant an approach to music-making which was then codified into a genre or style (mostly, guitar pop). For the purposes of this guide, though, I’ll be focusing on one ‘arm’ of Japanese independent music, that which has come to be known by some as psych-folk, characterised by quiet intimacy, playfulness, and an unpredictable approach both to songwriting and recording, such that the material here often takes surprising turns when you least expect it. That’s one of the many things that makes this music so endlessly compelling, beyond its surface whimsy and imperfect beauty.

The key figures in the history of the music, really, are Tori and Reiko Kudo of Maher Shalal Hash Baz, Shinji Shibayama of Hallelujahs and Nagisa Ni Te, Chie Mukai of Ché-SHIZU, and Saya and Ueno Takashi of Tenniscoats. They’ve mostly all played together in various configurations, often as members of Tori Kudo’s shapeshifting, avant-pop big-band Maher Shalal Hash Baz. The Kudos, and Shibayama, share a trajectory that reaches back to the Minor scene in Tokyo in the early eighties, where the Kudos made abstract, droning psychedelic music under the name Noise; they also participated in improvised sessions. The presence of Mukai connects to another thread of underground music in Japan, one of collective improvisation – she was a member of Takehisa Kosugi’s East Bionic Symphonia, and later was part of Vedda Music Workshop.

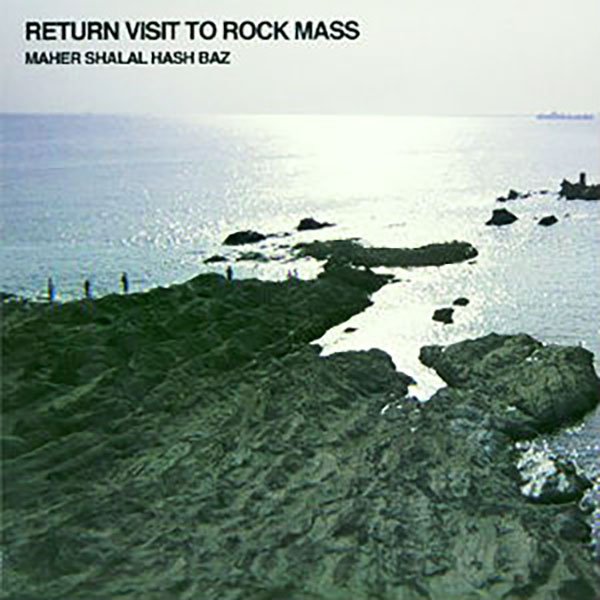

A little later, Shibayama self-released a post-punk EP under the name Team Spirit, before joining forces with Naoki Zushi, a forming member of noise renegades Hijokaidan, in Idiot O’Clock and Hallelujahs. The only Hallelujahs album, Eat Meat, Swear An Oath, is perhaps the formative document of the whole scene; it’s certainly one of the most gorgeous and uncompromising guitar-pop albums to be released, anywhere, in the 1980s. The other keystone document is the Maher Shalal Hash Baz triple-album set, Return Visit To Rock Mass, where Tori Kudo and Shibayama worked together to document as many of Kudo’s songs as possible. Decades later, it still feels completely idiosyncratic. Both albums were released on Shibayama’s Org Records, which would go on to document his group with partner Masako Takeda, Nagisa Ni Te.

Then, a curious thing happened; Maher Shalal Hash Baz caught the attention of music writer David Keenan, who covered them in The Wire and introduced their music to his friends Stephen McRobbie and Katrina Mitchell of Scottish independent music group, The Pastels. The latter would release a Maher Shalal Hash Baz compilation, From A Summer To Another Summer (An Egypt To Another Egypt), as the first release on their new label, Geographic Music; they’d soon follow this with a Nagisa Ni Te compilation, Songs For A Simple Moment, and would also release several more great Maher albums.

During that time, The Pastels also met Saya and Ueno from Tenniscoats, who’d been quietly supporting their friends like yumbo, Eepil Eepil and Andersens, by releasing their music on a label, Majikick. The Pastels and Tenniscoats would eventually collaborate on an album, Two Sunsets, while Tenniscoats would go on to tour the world and work with all number of artists: Jad Fair, members of Deerhoof, Maquiladora, Pastacas, Bill Wells. They were also ambassadors for their scene back in Japan, eventually setting up an online distribution store, Minna Kikeru, to release their music, and their friends’ music, digitally.

Guy Blackman, of the Australian label Chapter Music, was also a quietly significant figure, releasing an excellent and defining compilation of Japanese indie-pop, Songs For Nao, in 2004. This found its way into the hands of Markus Acher of The Notwist, who’s now a fervent supporter of the music, working with Saya on a series of compilations, Minna Miteru, for German label Morr Music, while also helping pull together compilations of artists like Andersens and yumbo, and reissuing an album by Gratin Carnival on his own label, Alien Transistor.

It’s been great to see the music finding supporters overseas. But some of the real thrill of this music is digging deeply into the self-releases, CD-Rs, cassettes and download-only albums that many of these artists seem to pump out on a semi-regular basis to their fanbase; sometimes, CD-Rs are only available as gifts when attending one of their small-scale gigs. There’s something that feels very right about that; the intimacy and communitarian spirit of the music reflected in its means of distribution. Here are twenty albums, mostly relatively easy to find and hear, at least online, that give a good sense of how this music has developed over the decades.