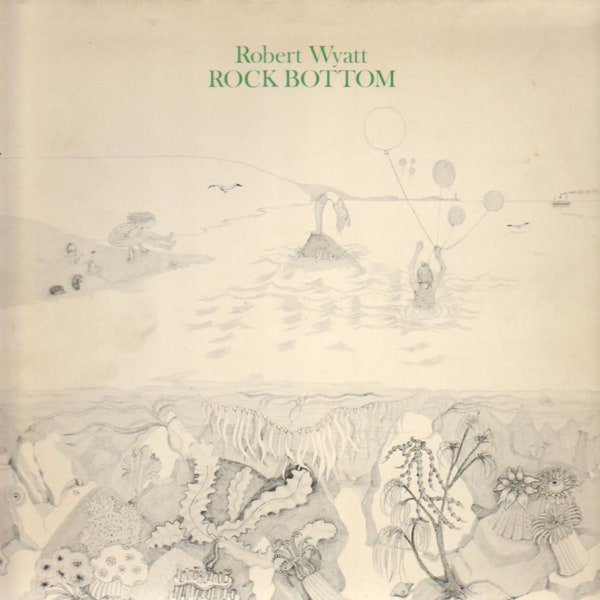

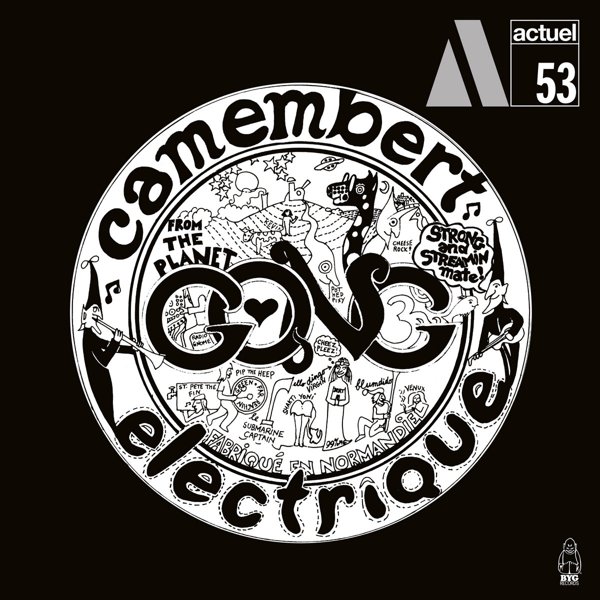

The way many of the musicians tell it, the 1970s Canterbury Scene wasn’t really a ‘thing’. There’s certainly some truth in this. Most of the musicians involved weren’t from Canterbury, a small city in Kent, the south-east of England, on the River Stour, so if you’re trying to pin a sound or sensibility down to geography, well, the scene’s membership gives lie to any such claim. Indeed, one of the key players, Daevid Allen of Gong, was from Australia. There’s also not really a distinct sound to the movement – Robert Wyatt’s reflective solo albums are a far cry from the musical rutting of some of the flights of improvisation by his former squeeze, The Soft Machine.

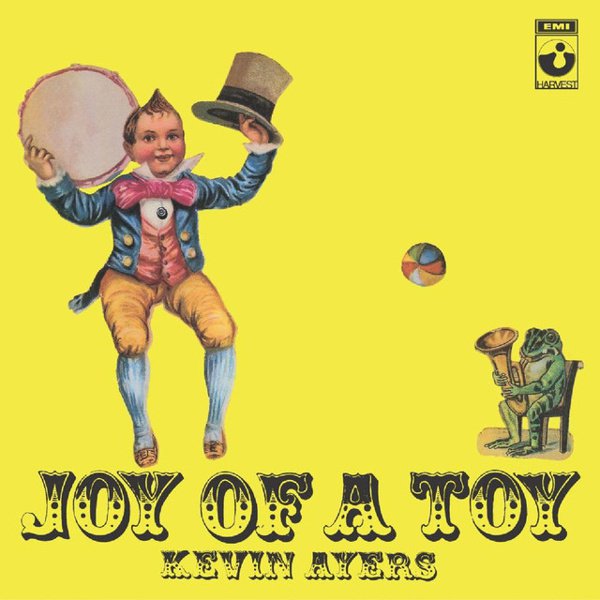

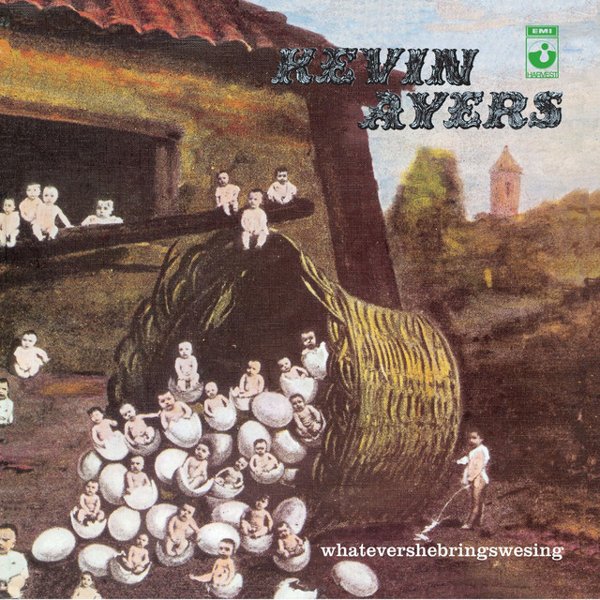

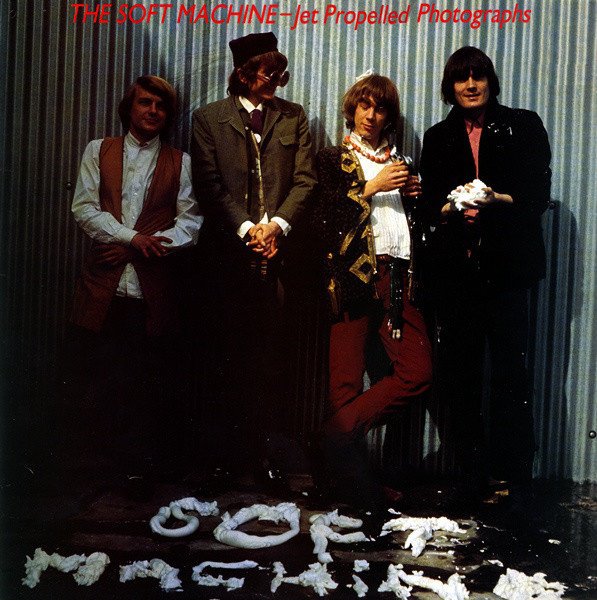

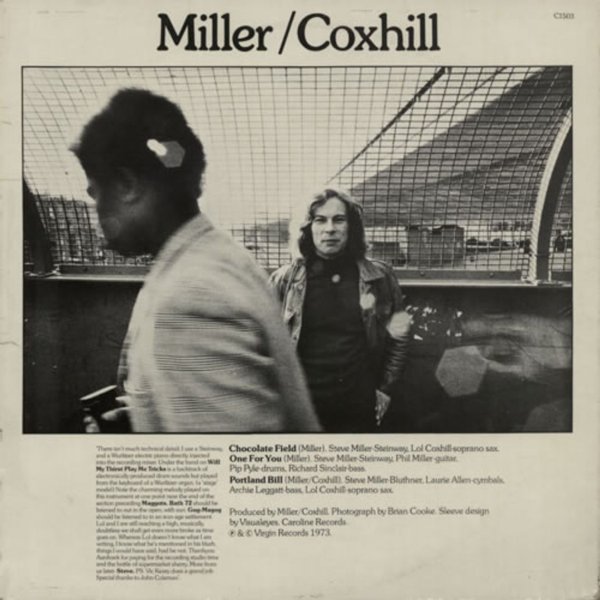

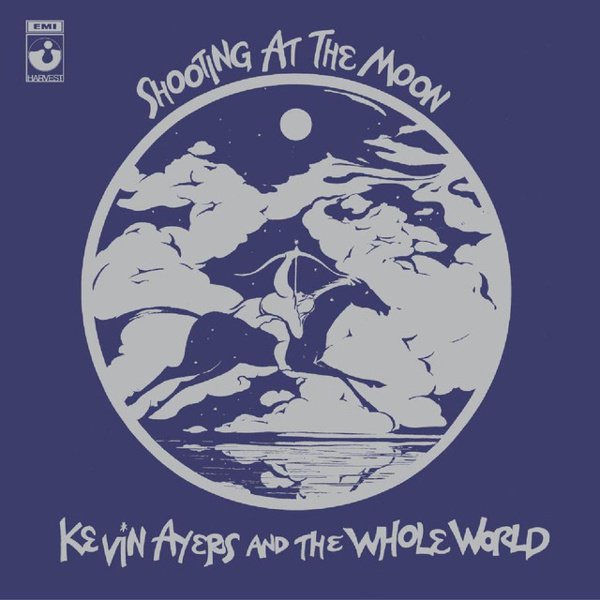

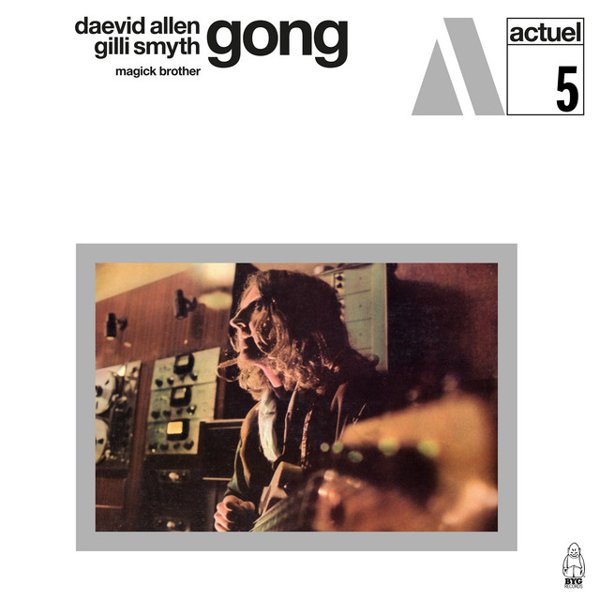

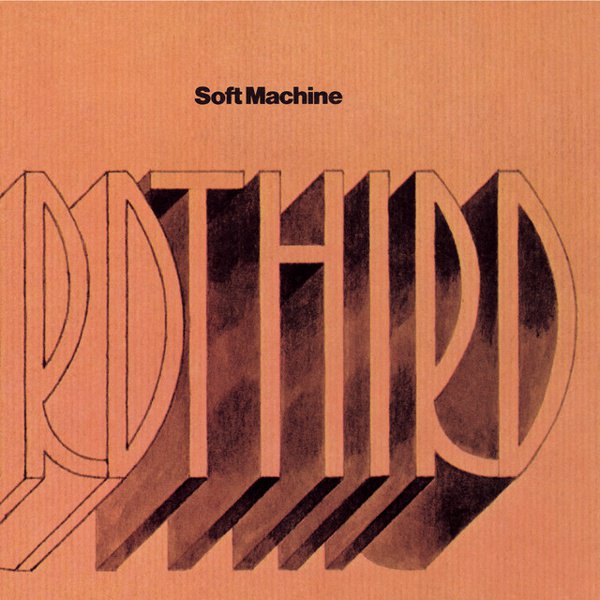

One thing that does seem to unite the various artists assembled, by others, under the Canterbury Scene aegis, is musical fluidity, both in listening habits (and thus influence), and in playerly capacity (and thus the music produced). Jazz was obviously big for many of the Canterbury Scene groups – it’s writ all over albums by The Soft Machine, Centipede, Hugh Hopper, Coxhill/Miller – but psychedelia is key, both in as psych-pop filigree and psych-rock grunt. Whimsy and play are significant – it’s hard to understand Gong without those facets – and also an ambient English pastoralism, one that takes root in albums like Kevin Ayers’s Joy Of A Toy, and that makes sense of the later, 1990s crossover between Canterbury and ambient house (both Wyatt and Ayers guested with electronica duo Ultramarine).

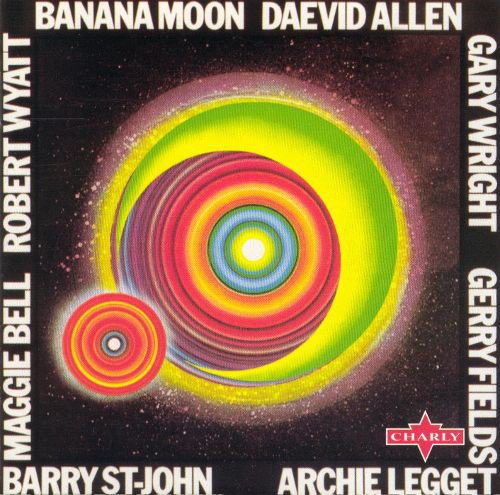

It’s The Wilde Flowers, formed in 1964 by Ayers, Wyatt, Brian Hopper, Hugh Hopper, and Richard Sinclair, though, who were key to the development of what’s now known as the Canterbury sound. It’s curious that, even in these early stages, some Canterbury classics were fully formed – Hopper’s song “Memories,” whose graceful melody and see-sawing musicality feels like the fount from which the Canterbury sound springs, was performed by the group. Ayers left the group when Daevid Allen turned up in town; Allen had already spent time in Paris, at the Beat Hotel, getting to know the likes of William Burroughs, and he bought that subversive energy to the mix.

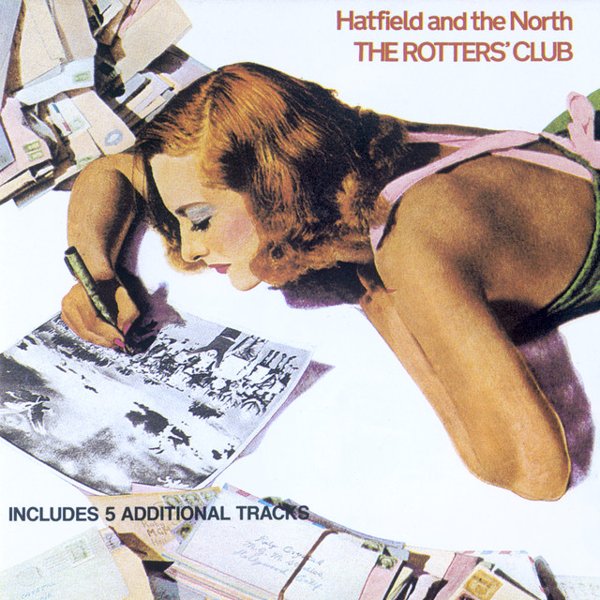

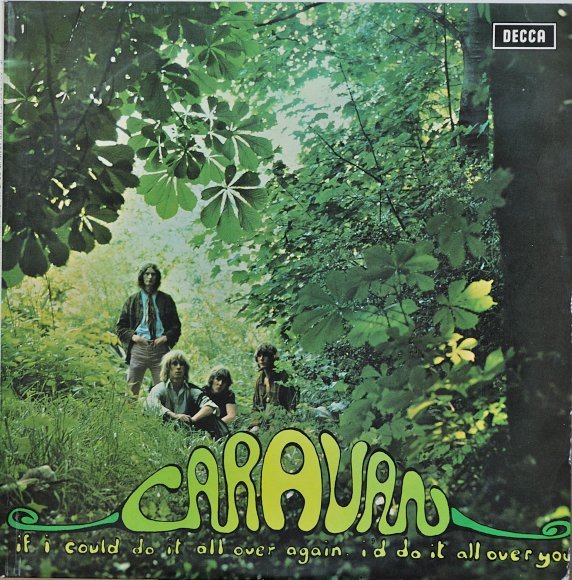

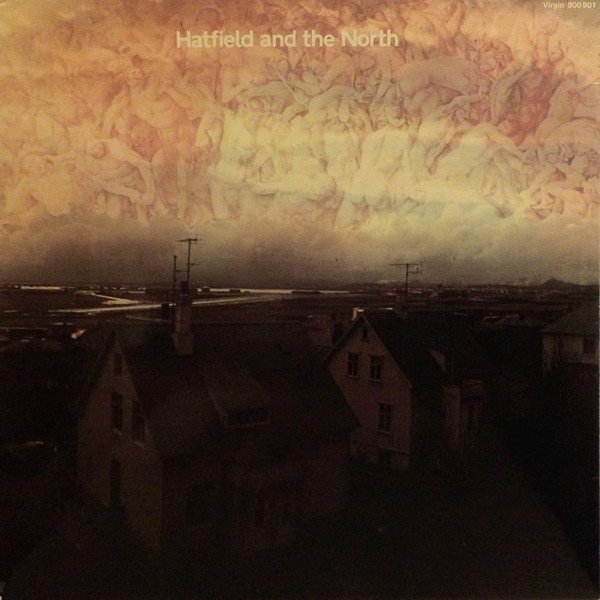

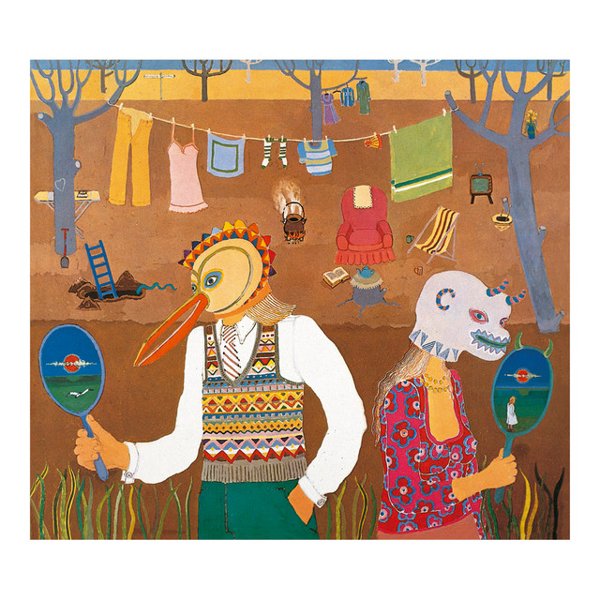

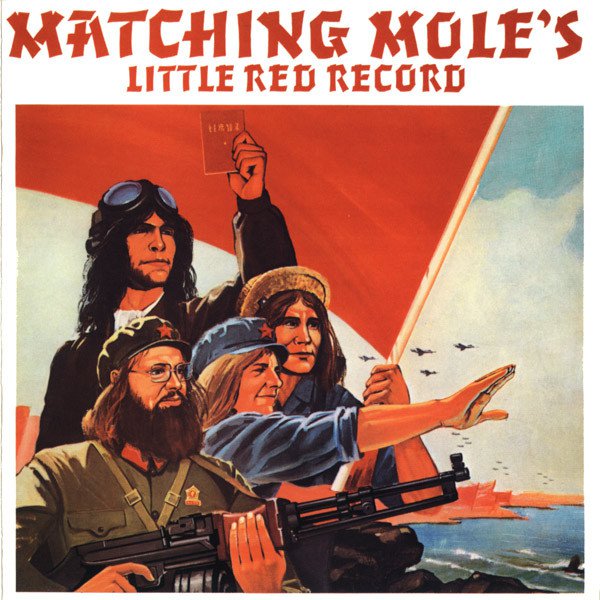

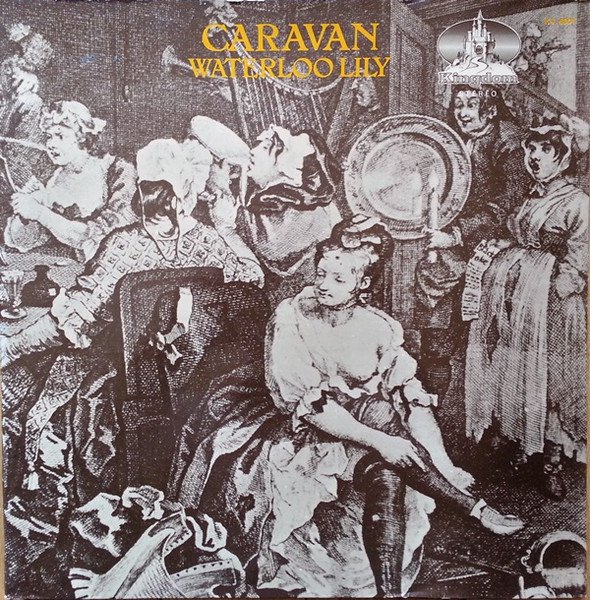

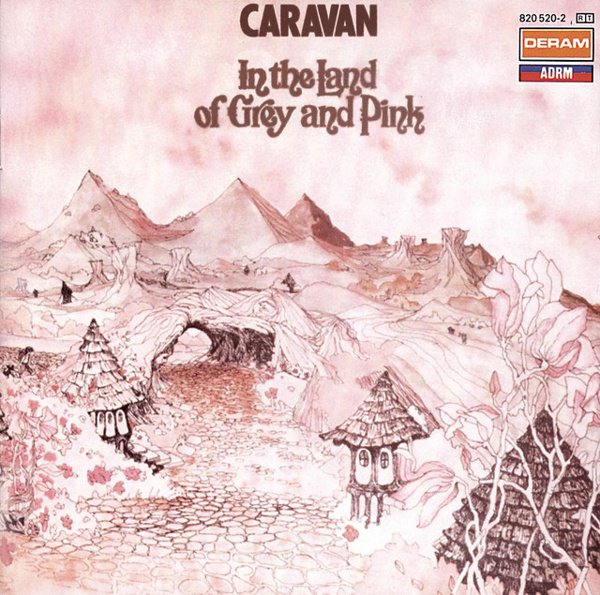

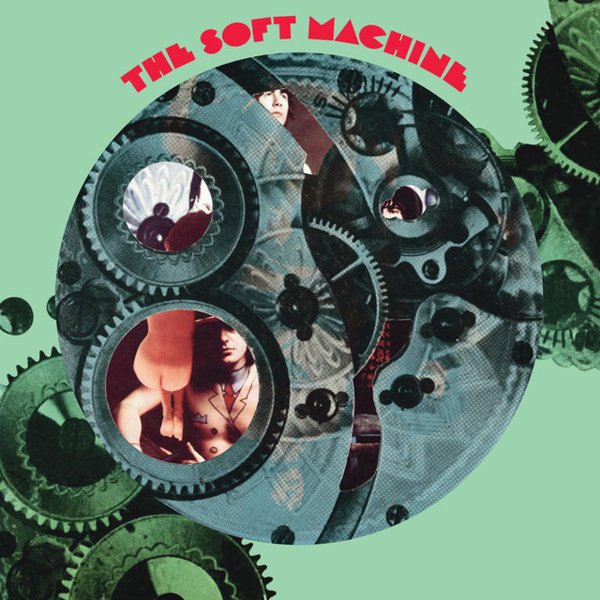

The Wilde Flowers moved through various line-ups – Graham Flight, Richard Coughlan, Pye Hastings, Dave Lawrence, and Dave Sinclair all joined at various points in time. Flicking through the mental rolodex of the various Wilde Flower memberships, then, you’ve got the formative alignments that led to The Soft Machine, Caravan, and Hatfield & The North, the three best-known, and most significant, of the Canterbury Scene and sound. If these groups shared anything, it was a sense of humour that sat somewhere between pataphysics, surrealism, and British slapstick; there are moments on many of their albums that are funny, but often in unexpected, unpredictable ways.

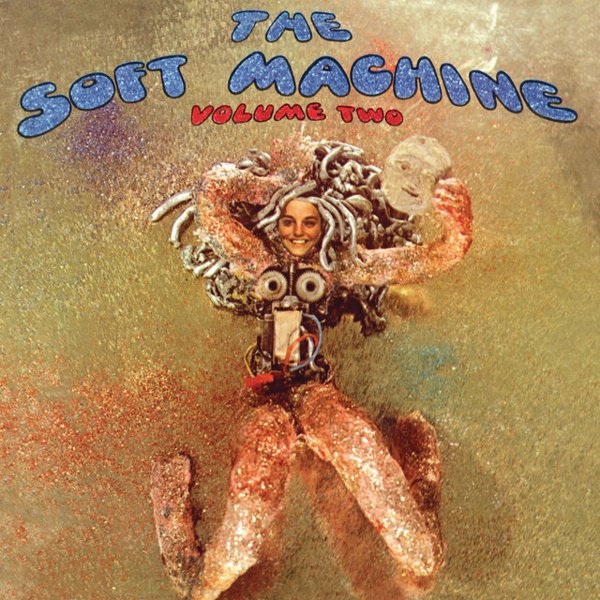

But that humour was matched with a tight sense of purpose, and a musical ability that meant the songs and improvisations, particularly in the late 1960s and first half of the 1970s, effortlessly walked the tightrope between musical proficiency and adept self-editing. On albums like The Soft Machine Volume Two, or the self-titled Hatfield & The North set from 1974, the playing is fluent and accomplished, but it never feels prolix. If anything got in the way of some of the later albums by the likes of The Soft Machine, it was a rutting, fusion-y need to do too much. This is why there’s often a mid-1970s cut-off point when people discuss the Canterbury Scene and sound; the music and the attitudes changed over time, and those key elements, of play and humour, start to disappear, or transmute into something different.

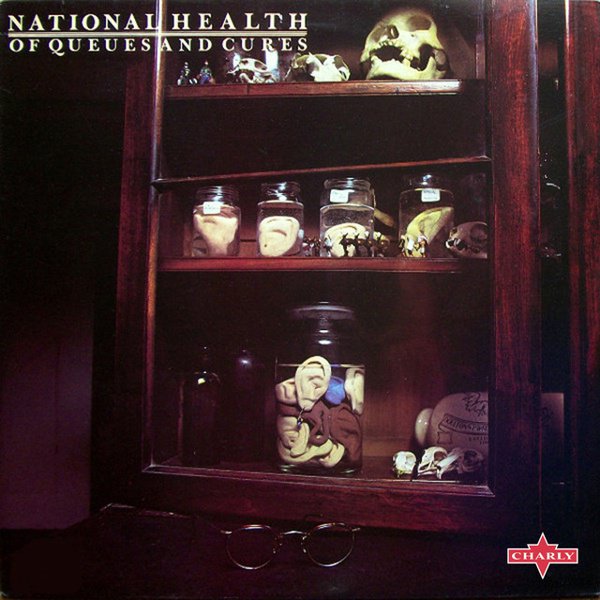

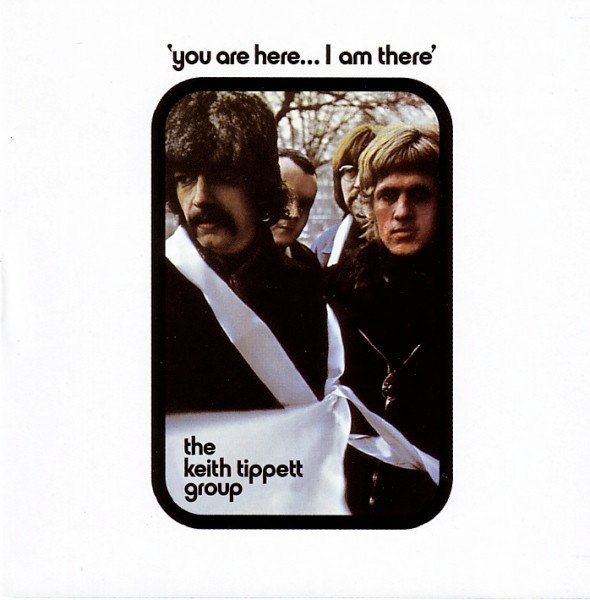

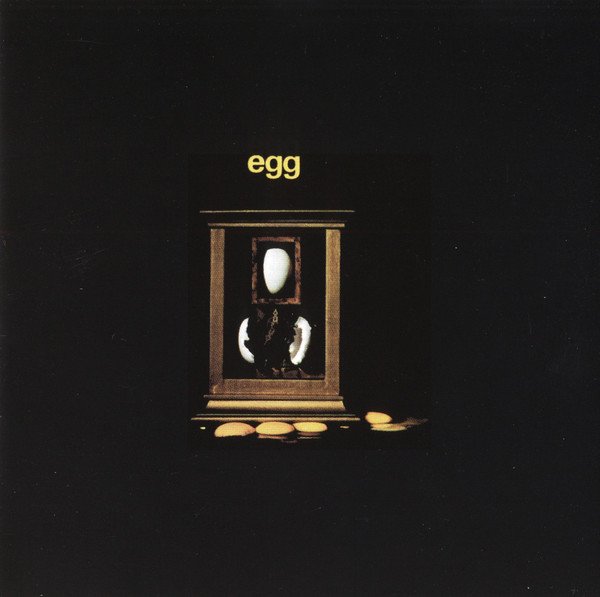

This list includes the key albums you need to hear to get a sense of the breadth of what the Canterbury Scene achieved, at its peak, and some outliers, such as the Coxhill/Miller set, or Centipede’s Septober Energy, where members of the Canterbury Scene, and/or aligned peers, make music that’s informed by lessons learned in those early years. It’s music that’s the very epitome of ‘serious play’.