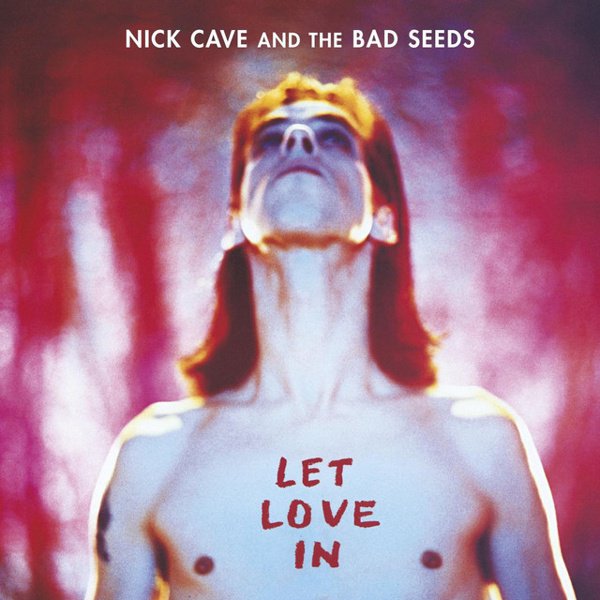

“He’s a creation of some sort, where you can’t even imagine that he could have parents,” Nick Cave once said about his one-time bandmate in The Bad Seeds, Blixa Bargeld. “You can’t even imagine what coupling of normal people could create that thing.” It’s certainly true that Bargeld, the German polymath who has helmed his group Einstürzende Neubauten (Collapsing New Buildings) for over forty years, is one of a kind. There is a defiance to his spirit, and a single-mindedness, that has served Bargeld well over his career – he seems to have an uncanny knack for finding the right situations, at the right time, and for navigating his way through the various impasses of a musical career with relative ease.

Most importantly, over the past five decades, he has blossomed into a songwriter of rare poise and fluency, maintaining a purity of creative vision even as some of his side-hustles – like his infamous series of advertisements for the German hardware store Hornbach – play loose with his legend. Watching early Neubauten clips, like their Liebeslieder video from 1980, or the wild footage recorded by the group on the Autobahn, released as part of the Wind-Up Tape collection, you wouldn’t necessarily expect this outcome. The figure Bargeld presents in the latter video – ratty hair, sallow skin, thin as a rake, in regulation leathers – is one of an outsider channelling urban desolation into a new, almost formless blues plaint, with the clutter of construction for a soundtrack.

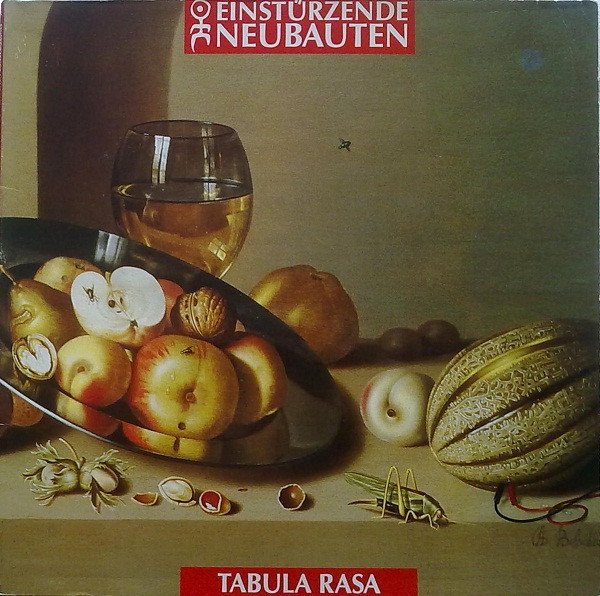

Einstürzende Neubauten often get called industrial, resulting from a reductive reading of their use of the left-behind detritus of society and its material resources – metals, springs, chainsaws, jackhammers, air pressure, etc. – as part of their extra-musical armoury. Bargeld has always been uncomfortable with the term, correctly noting that Throbbing Gristle invented and laid claim to the genre. If anything, Neubauten extends out of German post-punk, in particular the remarkable Geniale Dilletanten (non-)movement, which loosely aligned Neubauten with groups like Die Tödliche Doris and Der Plan. This all played out during the early 1980s, where an incredible number of creative artists gathered together in Berlin, making music and art, and in Bargeld’s case, also running a secondhand store, Eisengrau.

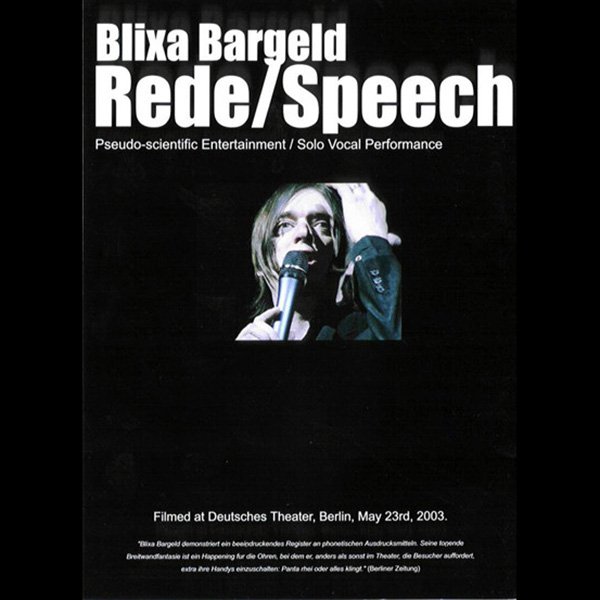

The most legendary Neubauten line-up is surely the one that piloted the group through the eighties and early nineties, of Bargeld, N.U. Unruh, F.M. Einheit, Alexander Hacke, and Mark Chung. Several of the other members had prior form in German post-punk groups like Abwärts, Sprung Aus Den Wolken, and Borsig, but the alchemy of this quintet was rare indeed. They worked hard during the eighties, releasing five albums, and touring internationally. During this time, Bargeld was also conscripted into Nick Cave’s group, The Bad Seeds, after a guest appearance on The Birthday Party’s final EP; Cave discovered Neubauten when he saw them on television, later saying, with echoes of disbelief still marking his face, “I’d never seen anything like it.” Bargeld would hold down the guitarist role for The Bad Seeds until 2003, and for an incredibly busy two decades he was an active member of both groups.

Over the past two decades, Bargeld hasn’t so much slowed his output as delved even more deeply into exploring the manifold nuances of his art. As Neubauten’s line-up changed over the decades, their music shifted too – more pacific, at times, with Bargeld’s voice and carefully sculpted lyrics often the centrepiece of their songs, though they are still more than capable of investing their music with the noise and fury of its early days. Neubauten’s and Bargeld’s projects are now often meticulously researched, the better to understand the myriad resonances of the material they’re working with. They’ve also explored the possibilities of existing outside of traditional music industry structures via their ongoing supporter / subscriber project.

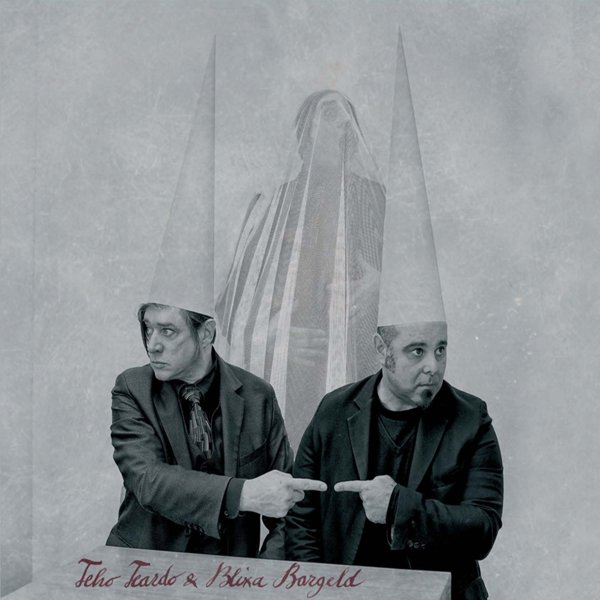

Bargeld has also collaborated with a number of other musicians, projects with figures as diverse as Italian composer Teho Teardo and German glitch pioneer Carsten Nicolai; he has also acted, and his unique scream has voiced characters in a number of films, including Stephen Sommers’ The Mummy. He crops up in curious places – the previously mentioned hardware advertisements; on cooking shows; as Grandmother Cash, on 2-Kut’s techno track “Rock That”; as a theatre and film composer; a guest vocalist with Die Haut, Anita Lane, Gudrun Gut and countless others. Behind that sardonic face, that poker rictus, lies a generous and thoughtful artist, one with a subtle sense of play, and a serious dedication to their art in all of its many voices.