Jon Savage explained the term well in his 2011 essay for Red Bull Music Academy: “Krautrock is the term most commonly used for psychedelic, expansive German rock, but it began as an insulting piss-take, coined by the British music press in the early 70s.” That phrase, in what may have been a détournement, became the title of a 1973 Faust song (a great one). It’s often replaced by “kosmische,” of which more later. I claim no authority in the naming here. It gets you to the music, which is the important part. Most of the musicians in Dusseldorf, Berlin, and Cologne hovering around rock in the early Seventies played together and knew each other. This was a small, familiar scene, like the early days of New York rap or the people who played CBGBs in the Seventies. It took bravery and smarts to make something from nothing without a support network. That’s one reason early community eruptions of a style or practice are often intense and rich: musicians were not doing something because other people were. They couldn’t be—nobody was. Krautrock is a goofy name but a legit grouping insofar as it indicates a bunch of bands in a certain place at a certain point in time who absolutely worked together and had at least some shared goals.

That said, in the lazy way that “post rock” often indicates nothing more than moody guitar instrumentals, “krautrock” has become shorthand for drumming like Klaus Dinger’s added to electronic noises. (Half the time, people just mean “Stereolab.”) Dinger himself hated the term “motorik” for his drumming and preferred, without explanation, “Apache.” (This could be a reference to the various songs named “Apache” but it doesn’t sound like them, so who knows.) The three things to pay attention to with krautrock: timekeeping, machines, and experimentation. And it helps to remember that krautrock is actually one of two terms, the other being “kosmische.” If pressed for time? Krautrock is steady eighth notes on the kick drum and mellow keyboard sounds; kosmische is synths and guitars through echo units and freeform jams. That seems dismissive but I only mean to bookmark big and important ideas with those little tabs. The kosmische spirit of unrestricted movement and the krautrock ability to establish a human regularity that mimics the steady attack of machines—these were major and wildly fruitful innovations that have never stopped creating new possibilities. It is not exactly clear which records contain which impulses, and many of these contain both. If you lose track, just go back to Kraftwerk’s career and start from the first Organisation album and proceed chronologically. By the time we get to Trans Europe Express, we’ve done it all.

Swing and shuffle and all other American forms of rhythm were simultaneously inspirational and irrelevant. German groups were turned on by the American and British rock & roll they heard coming from military bases, but they didn’t want to ape that music. They all decided to play in ways that wouldn’t have flown in Anglophone circles: harder, weirder, louder, less human. It is also key, and less-often mentioned, that krautrock became such a magic carpet ride for so many because it was often entirely instrumental. Partly because there was some trepidation about singing either in English or not-English, these bands mostly conveyed their visions with hands and feet. Even a band like Can, with not one but two singers, created music with only episodic vocals. All the better to dream along with. Songs, in fact, are only intermittently important. These bands had places to go and signposts were distracting!

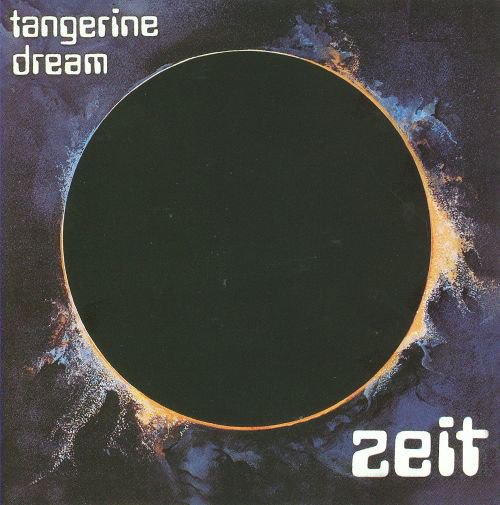

For reasons I’ve never quite understood, the Germans were more comfortable with synthesizers and drum machines. Their Anglo counterparts used them, but more timidly. The Germans went all in, making humans sound like machines and machines sound human. And the overall vibe of the experimentation was unmatched, perhaps the aspect that most makes a thing krautrocky. Politically motivated, open-minded, young, and bonkers—these are the kraut feelings. The krautrock buddies actually listened to how analog synthesizers and electric guitars really sounded—theirs was a gentle revolution of acceptance as much as action. The work keeps getting rediscovered because their respect for the gear was so pronounced. If you want to know what analog synths and guitars can do, there will always be concrete information for you in this catalog. Who listened to oscillators more lovingly than Tangerine Dream? Who respected the freakout more than Amon Düül II?

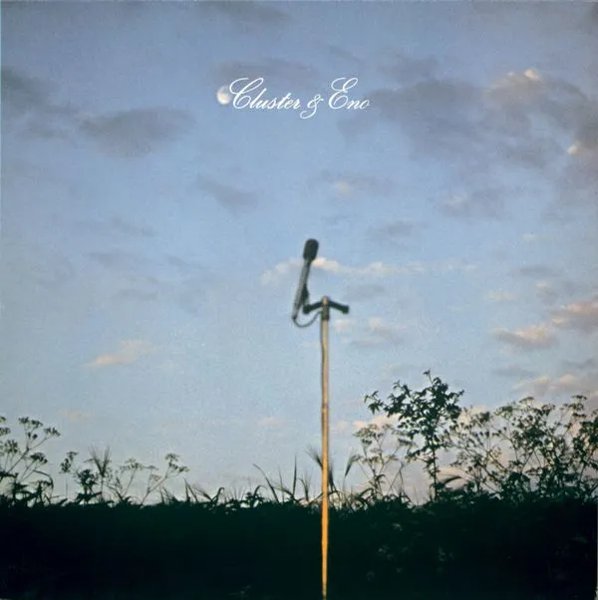

Honoring the gear is one way that Cluster and Harmonia and Kraftwerk all found new voices, as well as lasting power. Perhaps the effects of war made Germans more sensitive to the power of technology, as well as the role of radio in spreading liberating ideas. Can I have no explanation for, except they are maybe the most global of the Krautrock bands. Damo Suzuki is Japanese, Malcolm Mooney was entirely American, Jaki Liebezeit was German but half Motown at heart, Holger Czukay was from outer space, Michael Karoli could have been a psych player from Leeds, and Irmin Schmidt always felt vaguely Russian to me. There are no bands here you want to skip, and Can is the one where every single inch of tape is worth hearing. Their reach is as intense as that of Neu!, and then some. You find them smack dab in the middle of The Fall (the only band Mark E. Smith wrote a song about) and the Jesus and Mary Chain (who covered “Mushroom” for years). You find “Vitamin C” smack dab in the middle of hip-hop culture, and Stephen Malkmus has covered the entirety of Ege Bamyasi, not just “Vitamin C.” Their blend of dance music and improvisation would make them a jam band—except it doesn’t, which is down to how rarely they noodle and how deeply strange their vocalists always were.

Which brings it all back to Kraftwerk, connected at some level to almost all of the groups here. They are, undoubtedly, part of krautrock at least until Autobahn, when their current history begins. In fact, if you go see their excellent 3D live show, currently on the road, you will not hear any material earlier than Autobahn, which is when their krautrock simply becomes Kraftwerk music. They went on to become, even for those averse to hyperbole, one of the five or ten most important acts in the history of popular music. Kraftwerk are really simply their own category. That said, there are at least five albums from the years before Autobahn that find them absolutely into the hairy clutches of krautrock, right up to their ears in patch cables and sweet, sweet repetition.