The 20th century was a time when music was repeatedly and radically changed by technological advancements, large and small. The development of sensitive microphones allowed singers like Bing Crosby to stop bellowing and start crooning. The invention of the electric guitar: well, the reverberations of the first power chord are still being felt. The arrival of synthesizers and electronic keyboards in the late Sixties and early Seventies was just as important as either of those, and the musicians who fully embraced the possibilities of those instruments changed everything.

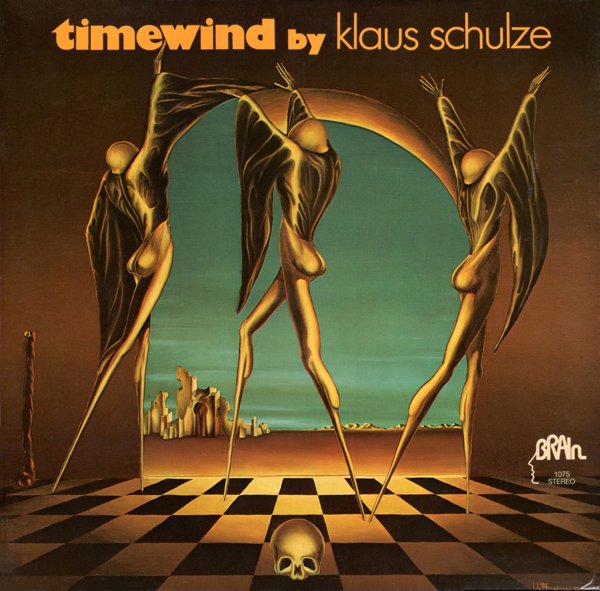

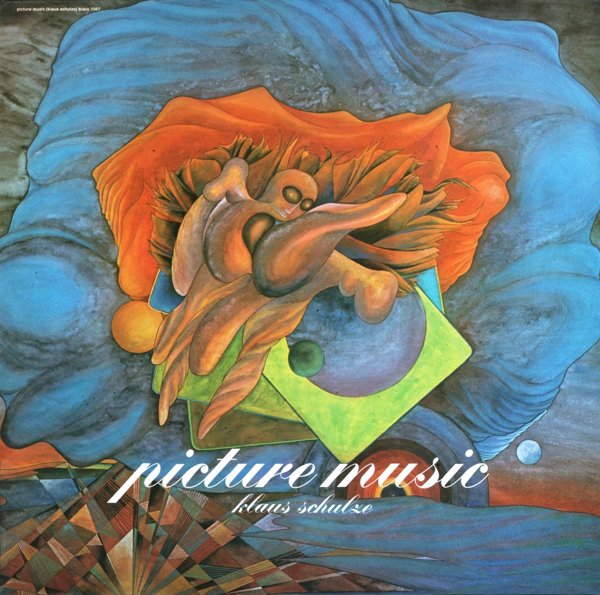

Klaus Schulze, who played guitar and drums in bands as a teenager, found his creative voice through keyboards and synths. Beginning in 1972, he made over 60 albums under his own name or one of a few pseudonyms, in the process pioneering the style known as “kosmische” (cosmic) music and inspiring generations of ambient and New Age composers. His work was used in films like Michael Mann’s Manhunter and Sofia Coppola’s The Bling Ring, and he scored the horror/exploitation films Angst and Barracuda, but his best-known work was a string of solo albums made in the Seventies.

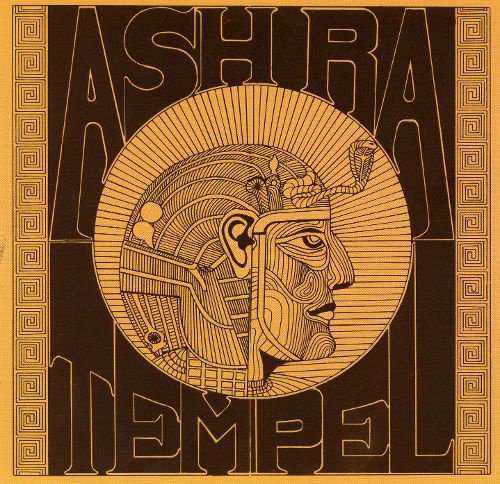

Schulze got his start as the drummer in Tangerine Dream; he can be heard on that group’s debut album, 1969’s Electronic Meditation, but the collision of two creative forces as strong as he and TD founder Edgar Froese forced a quick split. Schulze then became the drummer in Ash Ra Tempel, a trio with guitarist Manuel Göttsching and bassist Hartmut Enke. He played on their self-titled debut and 1973’s Join Inn, helping to pioneer the hard-driving yet ultra-disciplined grooves that would come to be known as “krautrock” before opting to focus on his solo work.

From the early ’70s on, Schulze commonly put out one or two albums a year, while touring extensively in Europe and Asia (he never visited, and never had more than a cult audience in, the US). His recordings tended to feature side-long tracks, which often consisted of elaborate melodic journeys laid over pulsing sequencer lines. Occasionally there would be a beat (either from him or Harald Grosskopf), and other instruments — cello, guitar — popped up here and there, but the synthesizers were always the focus.

Though he didn’t adapt to pop music trends, he did embrace new technologies, shifting from modular synths to smaller keyboards and later embracing sampling technology, drum machines, and whatever else came along. He also collaborated with a range of vocalists from Arthur Brown (of The Crazy World Of…) to Dead Can Dance’s Lisa Gerrard. In the mid ’90s, he joined forces with ambient composer Pete Namlook and bassist/producer/sound designer Bill Laswell for a series of eleven albums, The Dark Side Of The Moog, that were somewhat more beat-driven than his usual work. But his particular musical ideas — the lush melodies, the endless drifting backdrops, the sense that one was gazing through a portal at an infinite vista of stars — remained constant throughout his career.

Echoes of Schulze’s work can be heard in the music of those who came after him, like Steve Roach, and in the entirety of electronic subgenres like trance music and certain varieties of German techno. From behind his banks of keyboards, he changed the world. Miles Davis once said that all jazz musicians should get down on one knee on a particular day and thank Duke Ellington. Whether they know it or not, electronic musicians owe a similarly massive debt to Klaus Schulze.