Australian-born Lisa Gerrard, herself the daughter of Irish immigrants, has spoken about being raised in a Melbourne suburb where Greek immigrants also lived en masse, hearing much music from that country just as a matter of course. Besides proving to be a gifted singer, she also explored a variety of musical approaches, joining in Melbourne’s late 1970s/early 1980s post-punk scene already having begun to perform on what became a signature instrument, the yangqin, a Chinese equivalent of the dulcimer.

These experiences and much more formed the roots of became one of the most remarkable bodies of work in recorded music, as Gerrard – whose astonishing multi octave vocal range, ranging from contralto to mezzo-soprano, can truly be called operatic – proved to be open to and interested in creating music based in approaches and instruments from around the world, both in her own right and with a wide variety of collaborators, including a now well-established career in creating and contributing to movie soundtracks. Impossible to pigeonhole in any one approach and having spoken many times about the spiritual connection she aims to convey with music, she has created a body of work so vast it has almost perversely escaped true notice.

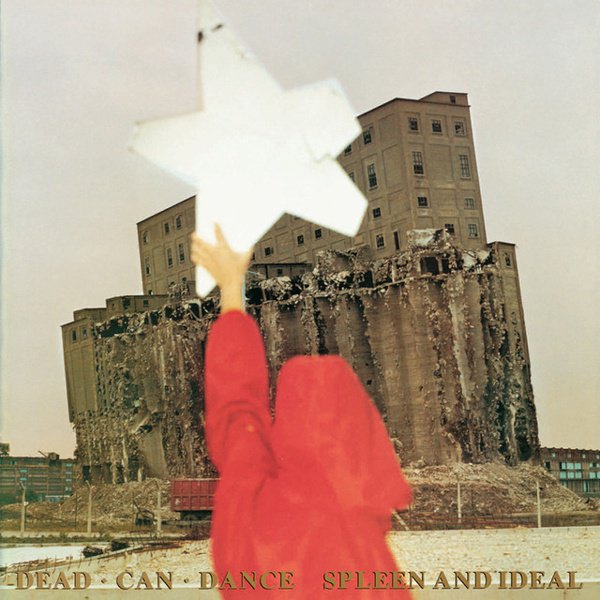

Meeting someone else in that Melbourne scene led to Gerrard’s first steps towards wider attention: the UK born, partially New Zealand raised Brendan Perry, who with Gerrard and two others formed the band Dead Can Dance in 1981. After relocating to London, the group signed to the 4AD label for their earliest releases, soon reducing down to the core duo of Perry and Gerrard along with a floating pool of key collaborators live and in studio. The group rapidly became emblematic for the label as a whole, winning initial acclaim in goth and underground music circles while demonstrating an astonishing ability to fuse a range of music across geographic space and cultural time. Both were accomplished singers, with Gerrard’s already jaw-dropping abilities seeming to only grow, whether singing in English, multiple other languages, or the wordless, glossolalic form she has described as ‘the language of the heart.’

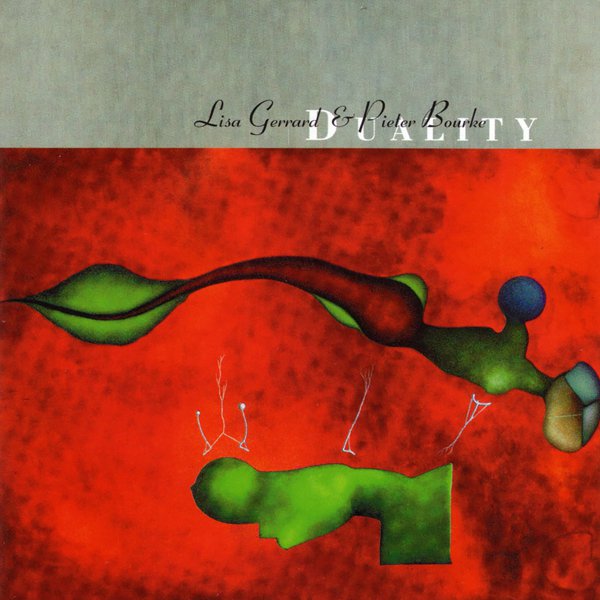

In what became a quiet sign pointing towards the future, some of their music began to appear as choices in film soundtracks, though the band itself dissolved during the 1990s as both began formal solo careers. Gerrard’s first release was The Mirror Pool, while her second, Duality, listed as a formal collaboration with Dead Can Dance percussionist Pieter Bourke, was the first in her now extensive catalog of such work with kindred musical spirits other than Perry. Meantime, Gerrard’s initial steps towards wider cinematic music prominence came via director Michael Mann, first with some selections from The Mirror Pool in Heat, then two from Duality in The Insider, along with a commission for some original music from her and Bourke.

It was the tragic early passing of Israeli singing legend Ofra Haza in 2000, however, which inadvertently led to Gerrard’s wider breakout beyond music-focused circles when Hans Zimmer approached her to replace Haza as a collaborator on the forthcoming soundtrack to Gladiator. The smash success of the Ridley Scott epic and its score, credited to both musicians, soon led to a continuing soundtrack career for Gerrard throughout the 21st century, either via further collaborative movie scores, including more work with Zimmer, as well as one-off contributions or full solo efforts, including her remarkable compositions for 2003’s Whale Rider. Even while she made a name for her efforts in this field, her general creative churn was equally strong, regularly working with a wide range of collaborators on various projects, ranging from German electronic legend Klaus Schulze to the Bulgarian State Television Female Vocal Choir.

In the midst of all this, beginning in 2005 she and Perry restarted Dead Can Dance on an irregular basis, first via a reunion tour and then with studio releases in following years as well as more touring, an extension of their early years together while finding a different balance. By the 2010s she was releasing new work every year, including solo, collaborative, and soundtrack music. As of 2022 she shows no signs of slowing down, with efforts ranging from contributions to Zimmer’s soundtrack to Denis Villeneuve’s adaptation of Dune to her recent albums Burn and Exaudia, both also collaborations, her vivid vocal and musical art in general a continuing testament to the power of tapping deep historical and emotional veins for a modern world.

![Gladiator [Original Soundtrack] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/5099471826845696_600.jpg)

![2:22 [Original Soundtrack] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/5735537491574784_600.jpg)