African musicians have a long tradition of experimenting with electronic sounds, ever since synths made their way to the continent — just look at musicians like Francis Bebey, Mamman Sani, or William Onyeabor. South Africa in particular has long been a hotbed for the development of new styles of dance music, from the first synthetic sounds of bubblegum to the deep bass lines of kwaito, all the way up to the world-conquering rhythms of amapiano. In recent years the growing availability of cheaper computers and production software has enabled people in all corners of the continent to make music in the bedrooms or DIY studios, resulting in a proliferation of small, localized music scenes rooted in tradition, as well as genre-defying electronic experimentations influenced by sounds from all over the globe.

For close to a decade Uganda-based Nyege Nyege has been shining a spotlight on these diverse currents of contemporary African music with scores of releases on their two labels, by fostering a local scene through residency programs, and of course the legendary music festival. Their sole commitment is to releasing “dope music,” without regard for geography or genre: their extensive catalog includes everything from breakcore to metal, royal Buganda music, electrified versions of traditional acholi from northern Uganda, South African Gqom, Kenyan rap, and politically charged vogue and techno.

While Arlen Dilsizian and Derek Debru founded Nyege Nyege Tapes in 2016, they’d been throwing parties and organizing residencies in Kampala since 2013. Their Boutiq Electroniq events both sowed the seed for Nyege Nyege and played a huge role in galvanizing Kampala’s budding electronic music scene with regulars like Hibotep and DJ Kampire. For Dilsizian and Debru the goal wasn’t simply to foster a scene for local artists, but also to increase opportunities for exchange that went beyond the traditional “Western artist samples local musician then leaves” dynamic.

They invited artists from Europe, the USA, and Africa to stay in the Nyege Nyege Villa, nurturing unions like that between UK producers Spooky J, sound engineer and synthesist pq, and Kampala’s Nilotika Drum Ensemble, which gave birth to the electro-percussion group Nihiloxica. In 2015 several artists from around the world, including Scotland’s Mungo’s Hi Fi, Berlin-based Chinese DJ Zhao, Fokn Bois from Ghana, and underground LA MC and producer Riddlore traveled to Kampala to take part in extended residencies with Ugandan and Kenyan artists. With both international and local artists on board the time felt right for the crew to take the next step and organize a multi-day event, so in October 2015 fewer than 1000 people gathered on the shores of the Nile for the inaugural Nyege Nyege Festival.

In many ways the festival was a disaster: heavy rains and flooding washed away tents and caused the latrines to overflow, and performances had to be postponed or canceled due to major technical issues. But a legend was born. Nyege Nyege offered a space like no other, where traditional music and cutting edge club sounds combined for a kaleidoscopic, chaotic, and endlessly joyful experience. The feeling of openness and diversity extended beyond the music, and away from the prying eyes of the Ugandan authorities people felt free to dress, dance, and express themselves how they wanted — queer folk included, a rare luxury in Uganda at the time.

Word about this unique new festival spread to neighboring countries and beyond, and over the next few years Nyege Nyege continued to grow, embracing its pan-African goals. At the 2016 festival keyboard maestro Mamman Sani played his first ever concert outside of Niger, and artists from South Africa, Burkina Faso, and Morocco joined musicians from the East African underground scene at the lush, slightly dilapidated, mind-bending Nile Discovery Beach venue.

Founded that same year, the new Nyege Nyege Tapes label captured the Nyege Nyege ethos. Two of their first releases were the result of past residencies, with Riddlore reworking a series of field recordings on Afromutations and Kenyan hip-hop legend turned producer Disco Vumbi aka Alai K teaming up with Nilotica Drum Ensemble and Ugandan instrumentalist Martin Juicy Fonkodi on Electro Boutiq (named after the residency).

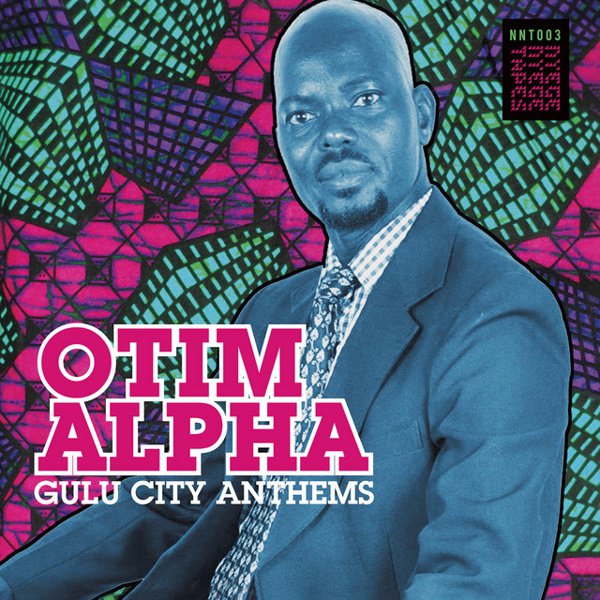

The third release resulted from one of the many hyper-local, DIY electronic scenes popping up even in the most remote areas of the continent. In Northern Uganda a handful of self-taught producers had been digitally recreating the sounds of Acholi music since the mid 2000s, in a bid to meet demand in the face of eroding tradition and the rarity of skilled musicians. Rather than being niche or underground though, electro-acholi has become the popular sound for weddings and celebrations in the region, largely taking the place of traditional live bands. Otim Alpha — a former bare-knuckle boxer, now one of the most “senior” and emblematic Nyege Nyege artists — and producer Leo Palayeng are two of the electro-acholi scene’s biggest artists, and Gulu City Anthems was the first release to compile their music and present it to an international audience.

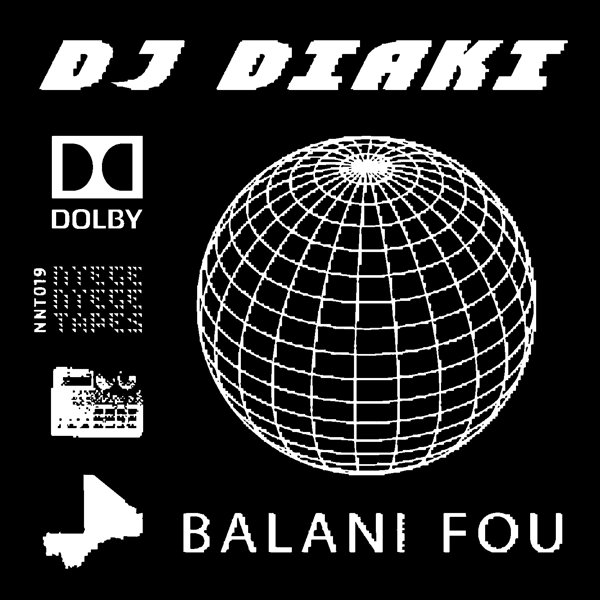

Like electro-acholi, there are other styles emerging in different parts of Africa that have one foot in tradition and another in contemporary electronic music, and that have become rather mainstream in their cities or towns. Nyege Nyege has helped introduce the rest of the world to the breakneck rhythms of singeli, a frenetic, 300bpm dance style that was born in the working class neighborhoods of Dar es Salaam, as well as the looping, chopped up balafon samples and hectic rhythms of balani from Bamako’s raucous street parties.

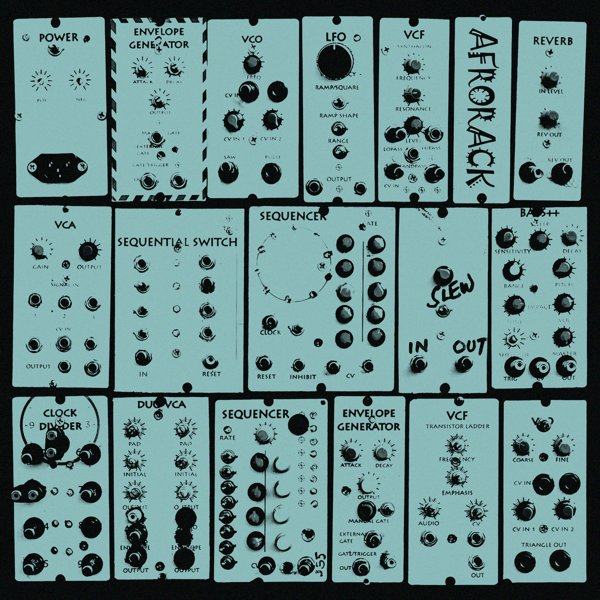

While Nyege Nyege continue to highlight this mix of regional styles and electronics, their releases reflect the sheer diversity of music that’s being made on the continent, including that with stronger ties to global experimental or clubbing music than any specific local sound. Producers Slikback and Authentically Plastic for example draw on footwork, grime, techno, and gqom, while Kenya’s Duma build upon Nairobi’s early 2000s hardcore metal and punk scene with elements of grindcore, industrial techno, and even gabber.

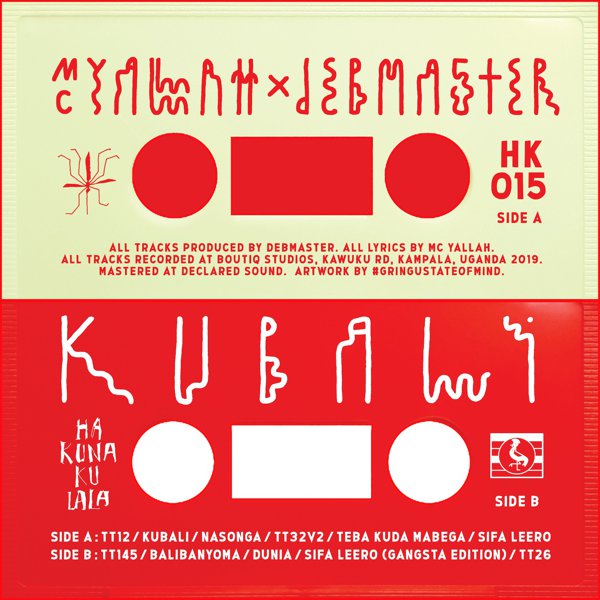

In 2018, a pivotal year which saw the festival explode in size and several artists embark on European tours, Dilsizian and Debru founded sister label Hakuna Kulala to provide a platform for these more club-oriented, experimental sounds. Despite some growing pains, Nyege Nyege is now considered one of the world’s best electronic music festivals, their residencies continue to foster collaborations between groundbreaking artists from all over the world, and both labels continue churning out mind-blowing, surprising music from around the continent and beyond.

![O Som do Labirinto [Original Soundtrack] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/5660594432114688_600.jpg)