Steven John Hamper, better known as Billy Childish, was born in 1959 and has been in a sort of cold war with the British cultural establishment since the 1970s. His copious output (scores of paintings, dozens of books, and countless albums under a head-spinning array of band names) is created entirely independently, keeping all gatekeepers and self-appointed authorities at arm’s length and thereby preserving his unique artistic vision.

Childish is an almost entirely self-taught painter; a poet and writer whose dyslexia went undiagnosed in childhood but has never hindered his ability to muster furious, heartfelt lyrics; and a rough, noisy guitarist and singer whose influences range from primitive country blues to cavemanlike garage rock. Though he’s licensed his music to a variety of labels over the years, including Sub Pop, Crypt, Ace (through their subsidiary Big Beat), Sympathy For The Record Industry and more, a lot of it has come out on his own Hangman imprint. In recent years, much of his back catalog has been reissued by the venerable UK punk label Damaged Goods.

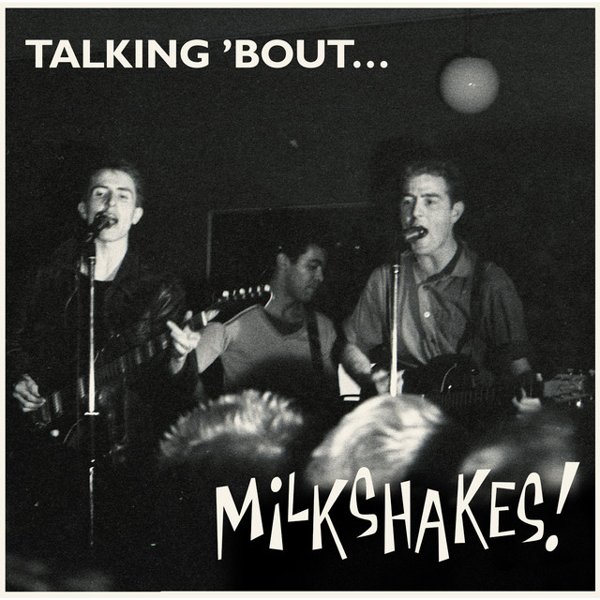

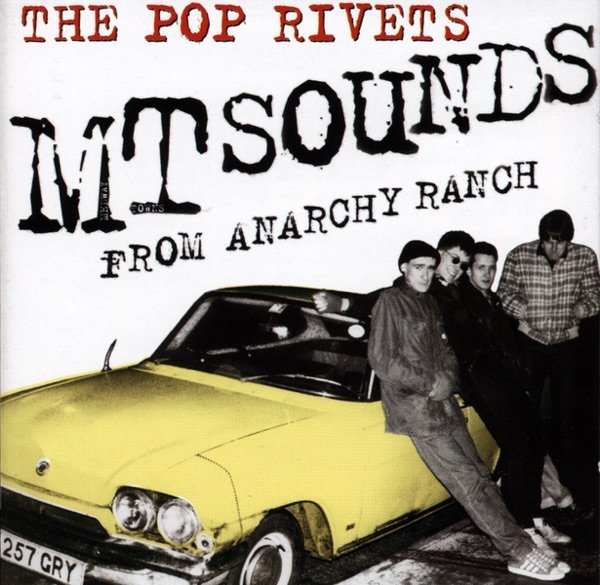

Childish’s first band was TV21, who later changed their name to the Pop Rivets. Their debut album, 1977’s Greatest Hits, was the first truly independent UK punk LP. Their music was artier and more complex than almost anything he’d do afterward; “To Start, To Hesitate – To Stop!” prefigures postpunk before punk itself had even gotten off the ground. The Pop Rivets broke up in 1980, and Childish immediately formed his next group, the Milkshakes, who played in a consciously retro 1960s garage-rock style. He wasn’t yet the visionary/artistic dictator he’d eventually become; the Pop Rivets’ songs were mostly co-written with guitarist Will Power, and the Milkshakes found him sharing songwriting and lead vocal duties with Mickey Hampshire. Had the Milkshakes’ songs been released in 1964 instead of 1982, they might well have charted, but at the time their sound was a determined act of rebellion against the moment.

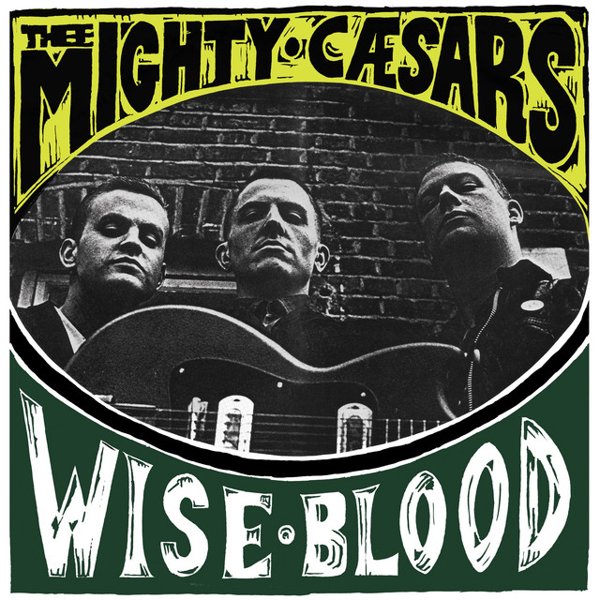

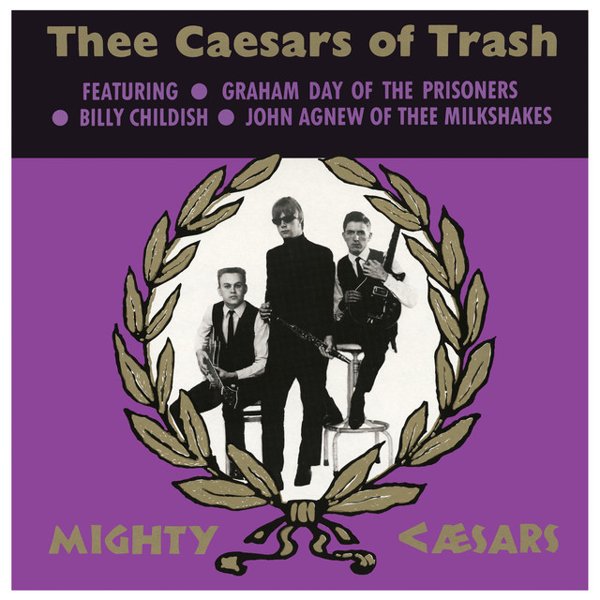

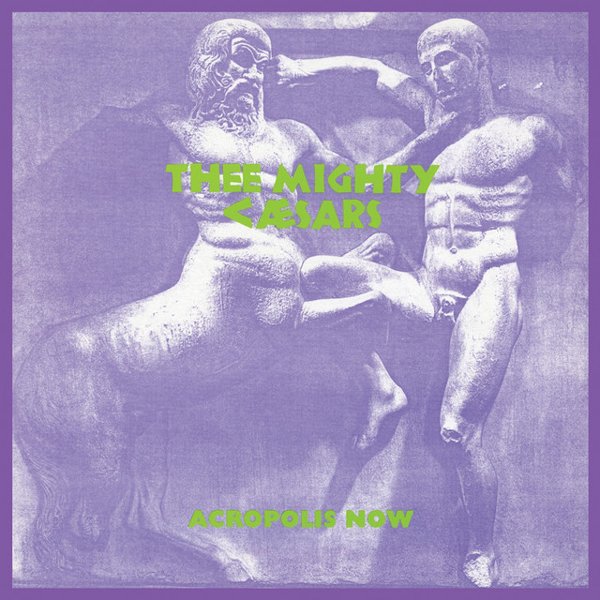

Childish truly came into his own in 1985, when the Milkshakes dissolved and he formed Thee Mighty Caesars with bassist John Agnew and drummer Graham Day. Day was soon replaced, though, by longtime Childish confederate Bruce Brand, who’d been in the Pop Rivets and the Milkshakes. Thee Mighty Caesars made noisier, more primitive music than the Milkshakes had, albeit still in a ’60s-indebted garage rock style, and their albums featured witty titles like Beware The Ides Of March and Acropolis Now. After six albums in five years, they broke up, and Childish and Brand recruited bassist Alan Crockford from another, similarly inclined local band, the Prisoners, and formed Thee Headcoats.

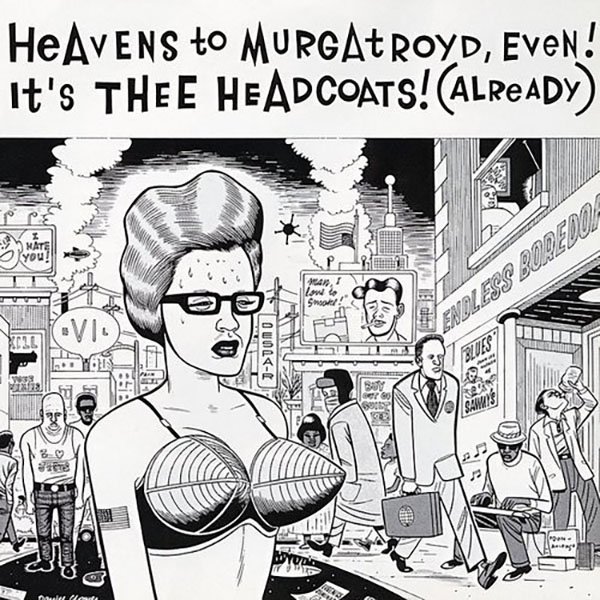

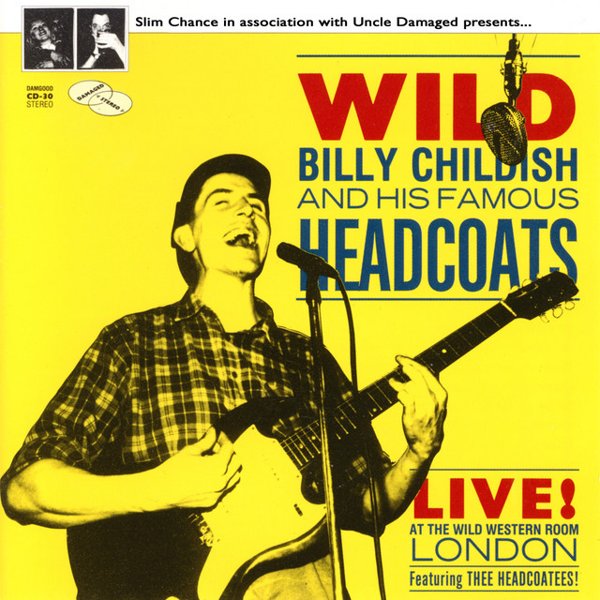

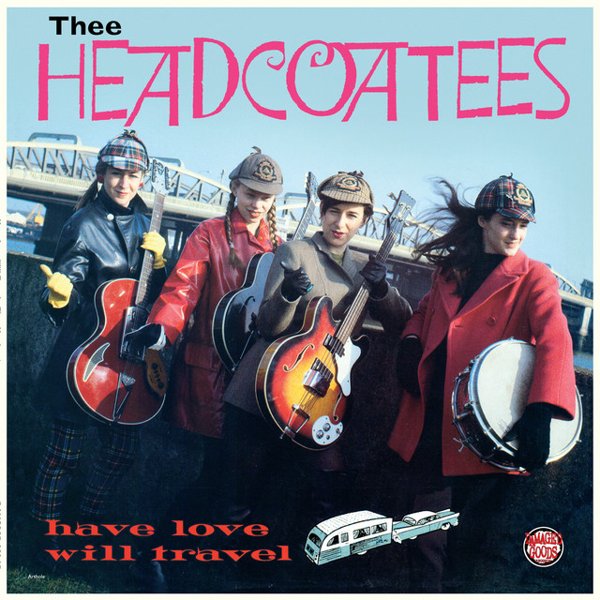

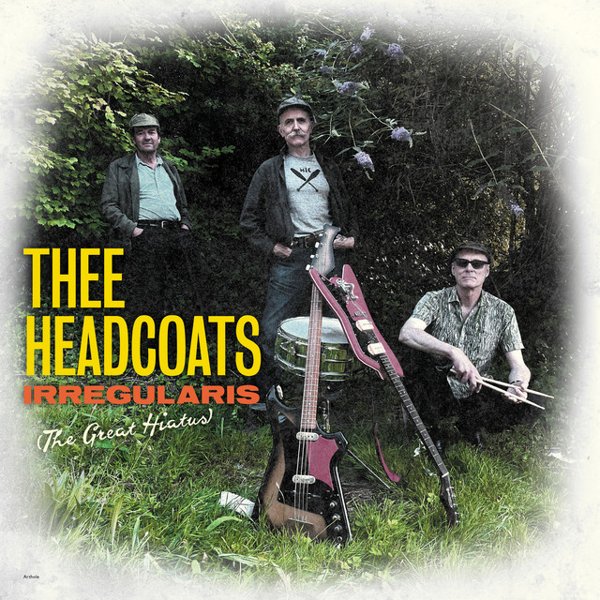

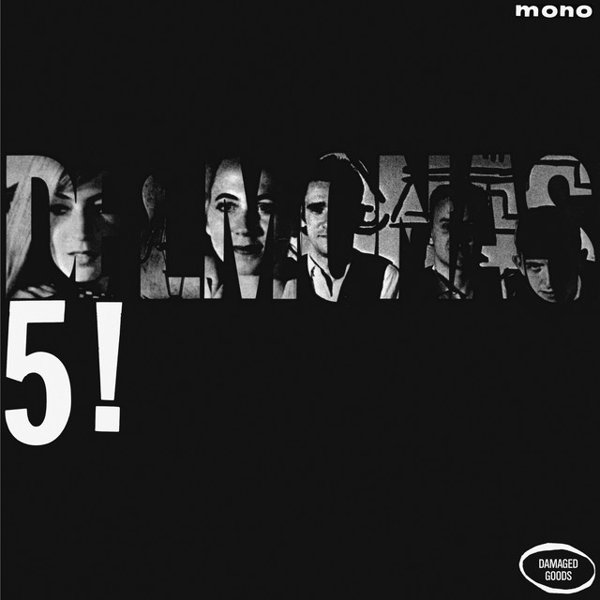

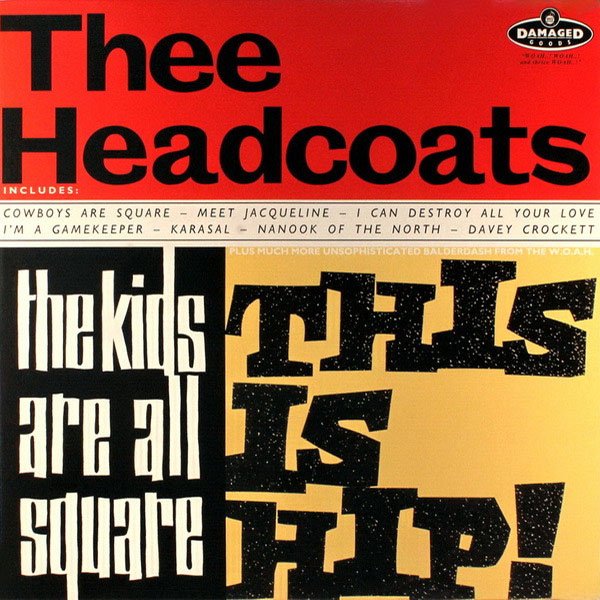

Thee Headcoats were Childish’s longest-running and most “successful” band. Visually recognizable thanks to their Sherlock Holmes-esque deerstalker caps, they made more than a dozen albums between 1989 and 2000, each one a short blast of high-energy, crudely recorded guitar-bass-drums garage rock, occasionally leavened by a dash of electric organ or some female backing vocals courtesy of Thee Headcoatees, a quartet (later a trio) of enthusiastic amateurs. Sometimes they’d take a slight stylistic detour; their debut album, Headcoats Down, included “Child’s Death Letter,” an acoustic blues wail. Thee Headcoats’ catalog included albums on Sub Pop (Heavens To Murgatroid, Even! It’s Thee Headcoats (Already)) and Crypt (Beach Bums Must Die), and enabled Childish to take his act on the road to the US and beyond. This period was arguably his peak of both output and prominence; the Sub Pop compilation I Am The Billy Childish, subtitled “50 Songs From 50 Records,” came out in 1991. (It still serves as an excellent starting point, with 2009’s Archive From 1959 — The Billy Childish Story a worthy sequel/companion.) He was writing so much material that he began putting together female vocal groups (the Delmonas, Thee Headcoatees) to sing them, with his current band — Thee Mighty Caesars or Thee Headcoats — serving as backing musicians.

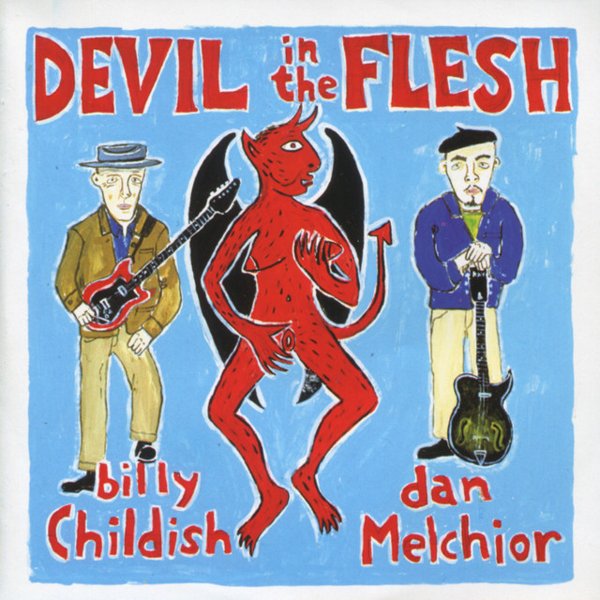

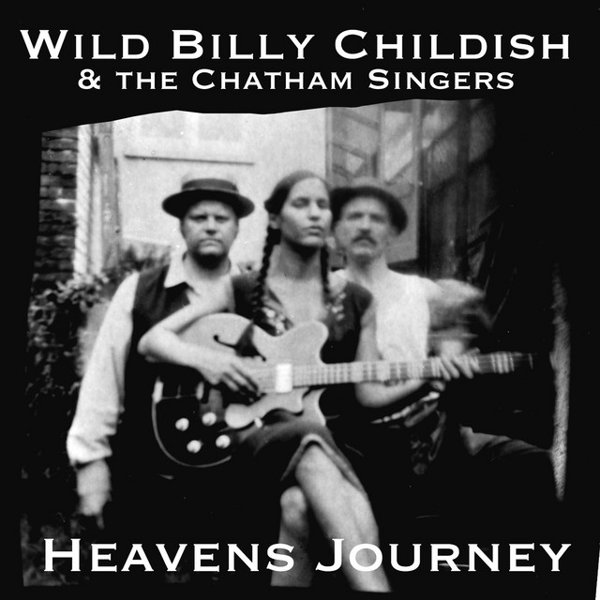

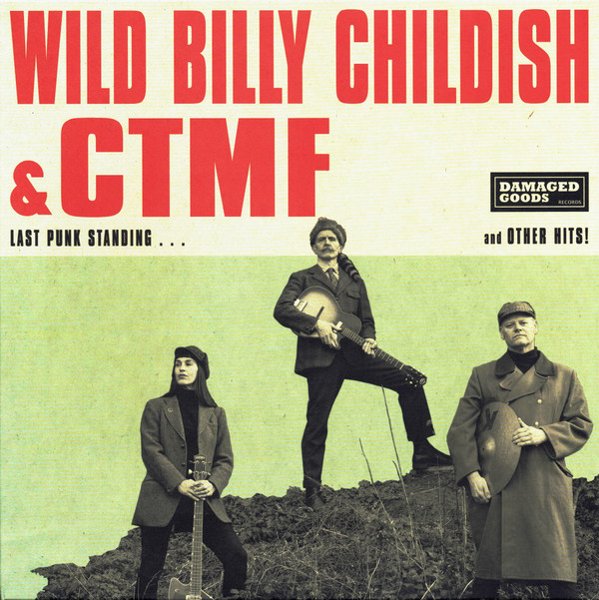

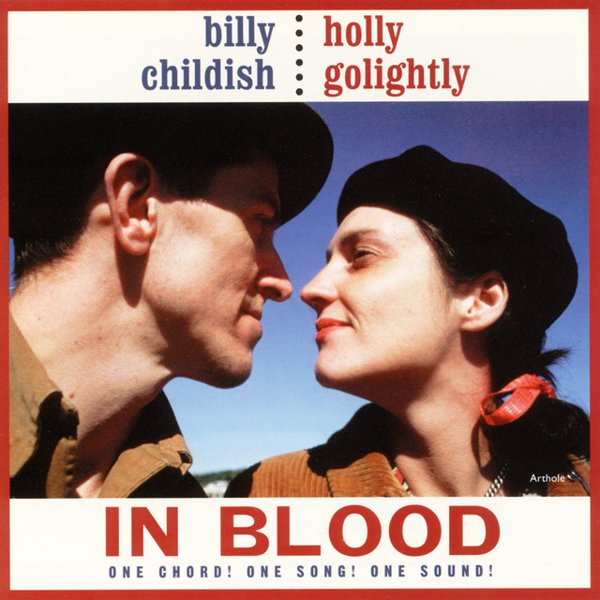

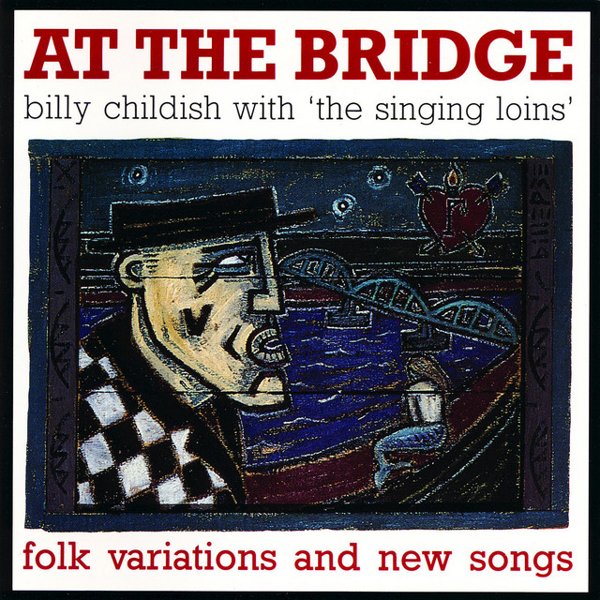

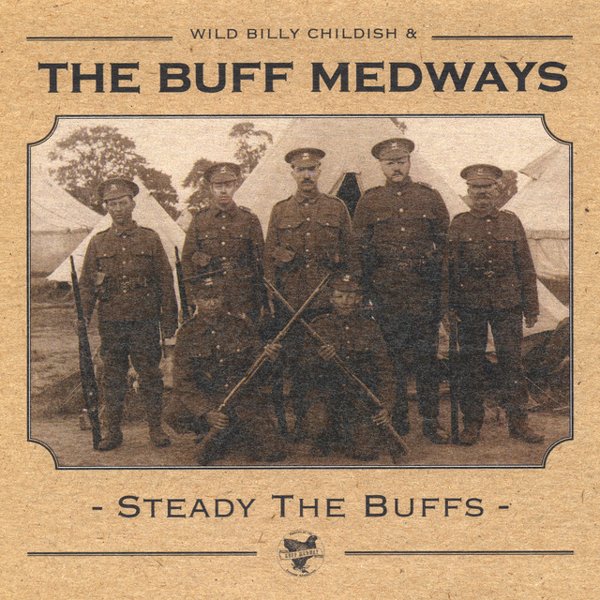

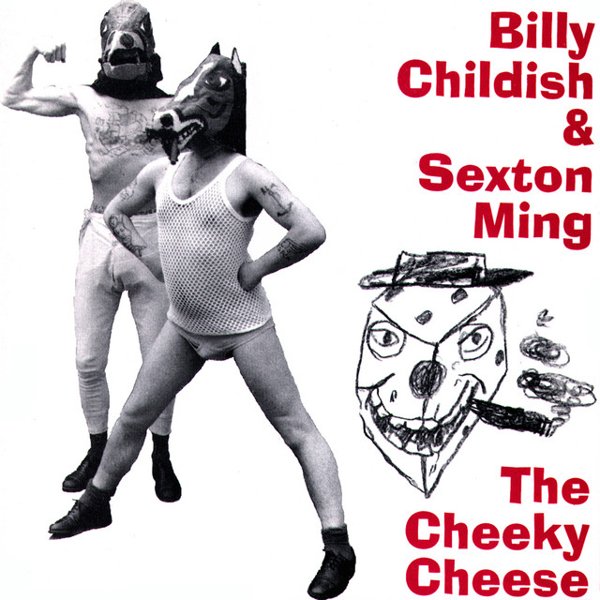

While continuing to pump out garage rock records, Childish has diversified his output quite a bit over the years, recording spoken word albums, collections of country blues and English folk, duets with former Headcoatee Holly Golightly, collaborations with fellow poet Sexton Ming, and more. His latest groups, the Buff Medways (named for a breed of rooster), the Spartan Dreggs, and the CTMF (which stands for Chatham Forts) produce music of greater sophistication than his ’80s and ’90s output, largely due to the bass playing and backing vocals of his wife, Julie Hamper, but his unique, keening/ranting voice and working-class-blues lyrics — which manifest an almost Beckettian black humor at times — remain instantly recognizable. Billy Childish will likely continue to make art until he drops dead, and/but the more of it you investigate, the more varied and fascinating it reveals itself to be. Below, 20 albums to barely get you started.