While ‘collective improvisation’ is only one of many terms used to describe the music in this guide, it strikes me as a particularly useful genre designation, indicating as it does both the group nature of most all the music explored here, and its grounding in improvisation as both a practice and a broader ethos. While there’s some overlap with ‘free music’ and ‘free improvisation,’ the collective tends towards groupings of broader membership than the usual trio or quartet formations that populate those fields. What’s common to the music here, then, is a tendency toward subsuming the individual and the ego to the group effort, a tendency towards deploying multiple, oft-unexpected sound sources, and a kind of ‘considered wildness.’

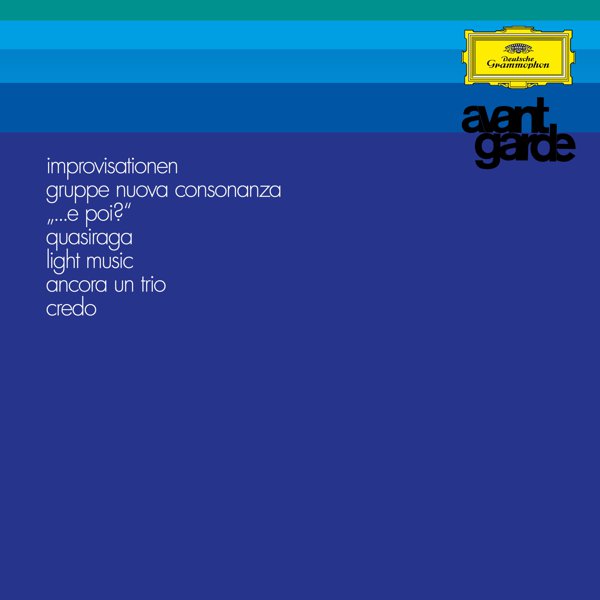

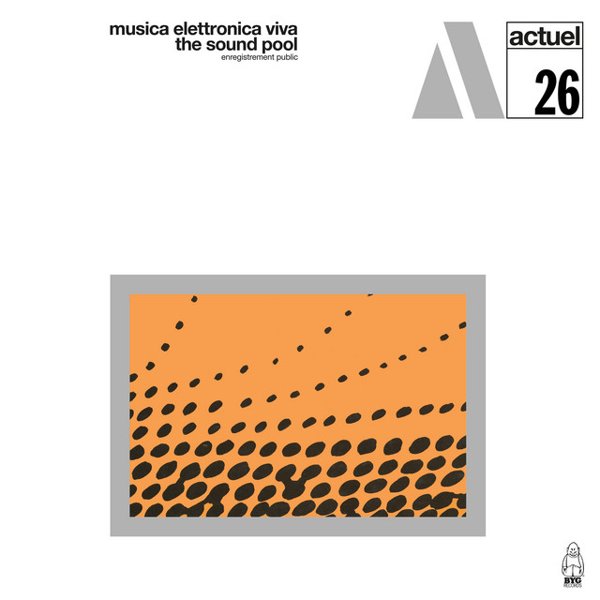

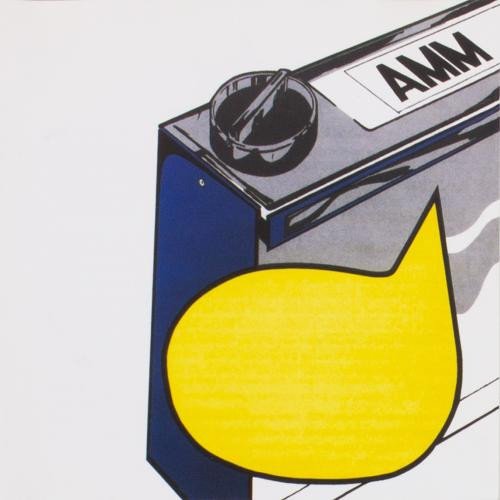

Collective improvisation crystallised as a genre of sorts in the late sixties, thanks to the explorations of groups like AMM, MEV, and Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza. Several factors informed the music. Firstly, many of the players came out of jazz and had been unshackled by the explorations of African American free jazz, but wanted to push things in a different direction. Secondly, there was often an interface with modern composition (particularly the work and ideas of John Cage) and the academy. Thirdly, an interest in multimedia arts and performance was instructive – some groups featured performative aspects; a few included members of art groups like Fluxus.

The conflation of several technological developments helped, too – greater access to amplification, consumer electronics, and in-the-moment sound processing all had a part to play. The music was also often informed by engagements with what would, then, have been blithely called world music; there was also some interest in improvisation as a ‘natural’ form of folk expression. Groups like AMM and The Scratch Orchestra would also go through political ructions that indicated some broader thinking around socialist and communist perspectives.

So, there’s a lot going on around collective improvisation. That it would gather momentum in the late sixties and seventies suggests an allegiance with broader, counter-cultural movements too, from student protest to psychedelia, drug use and hippie consciousness. Indeed, AMM shared stages with the early Pink Floyd, and were a noted influence on Paul McCartney. But those broader mainstream-cultural interfaces seemed the exception, not the norm, and the music was left to stew, ferment, and develop new, curious ways to explore the limits of improvisatory, non-idiomatic freedom, for decades.

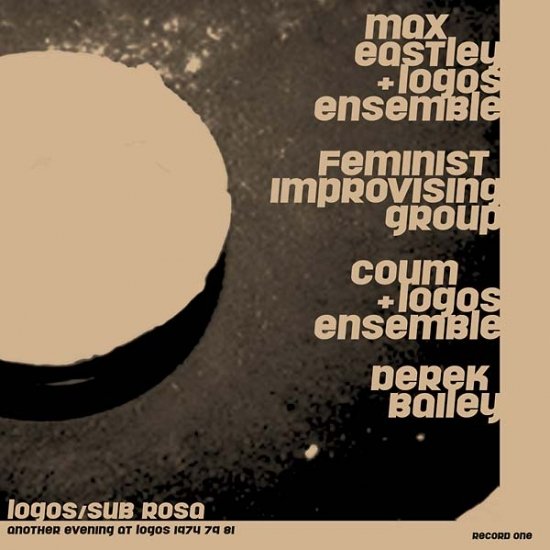

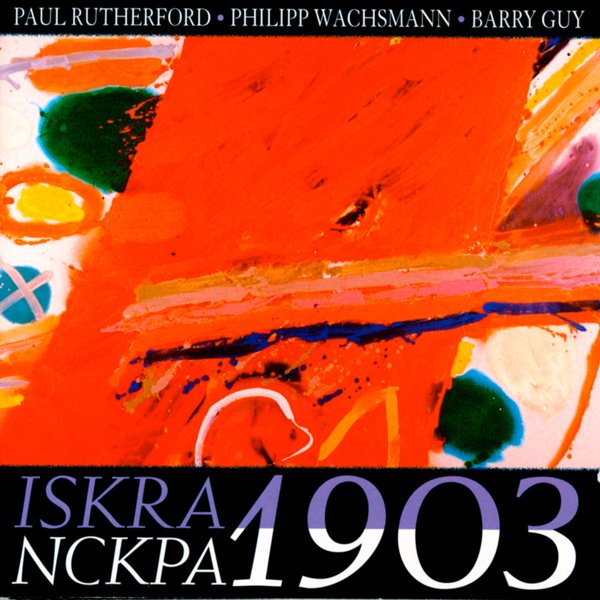

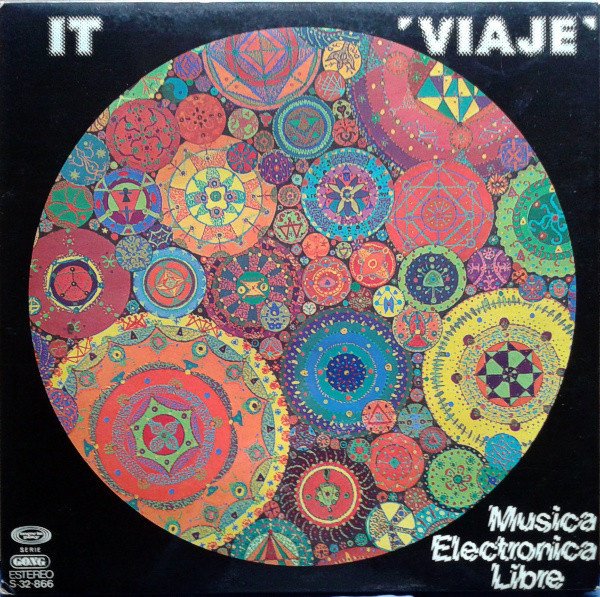

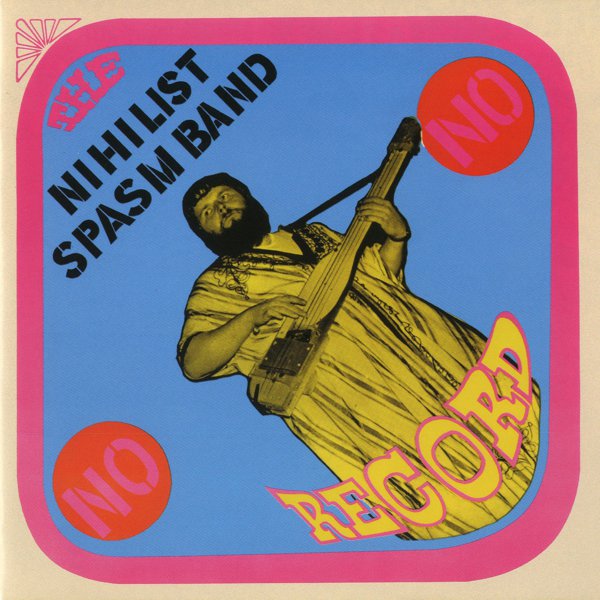

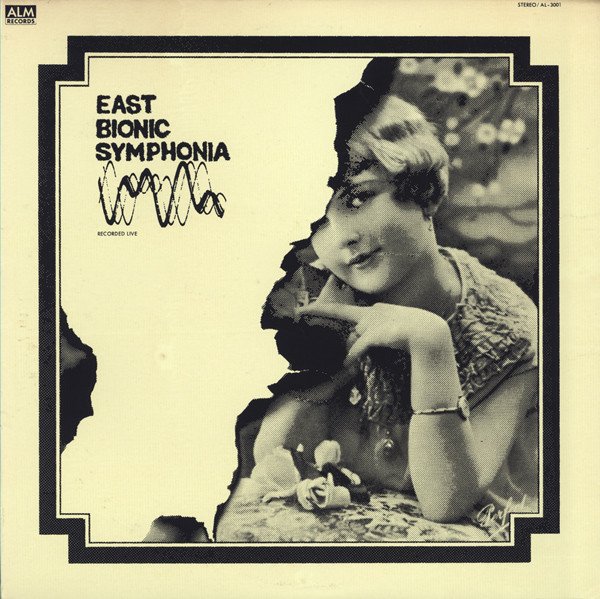

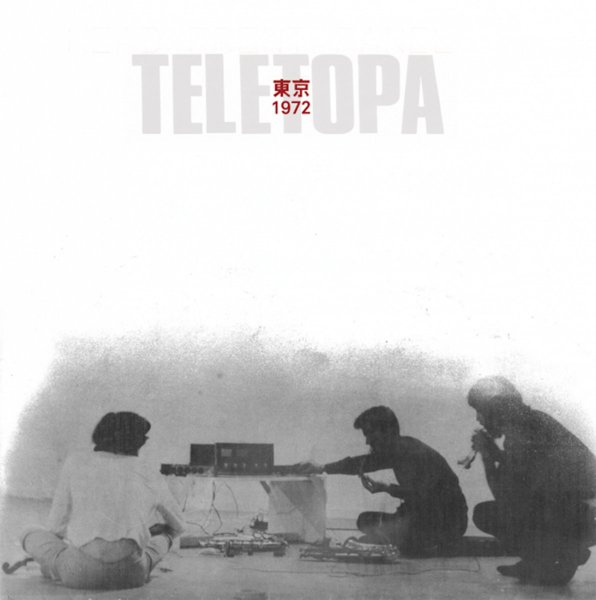

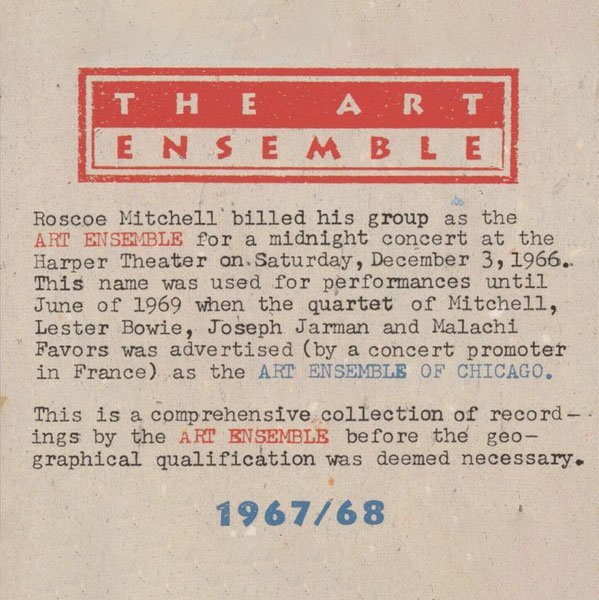

This guides features key albums from some of the most important groups in the field – AMM, MEV, Nuova Consonanza, The Scratch Orchestra – along with some lesser-known, but just as significant developments, an exemplar from the space where this music intersects with free jazz (The Art Ensemble), and some contemporaneous music that shares a spirit, or some membership, with collective improvisation ensembles.