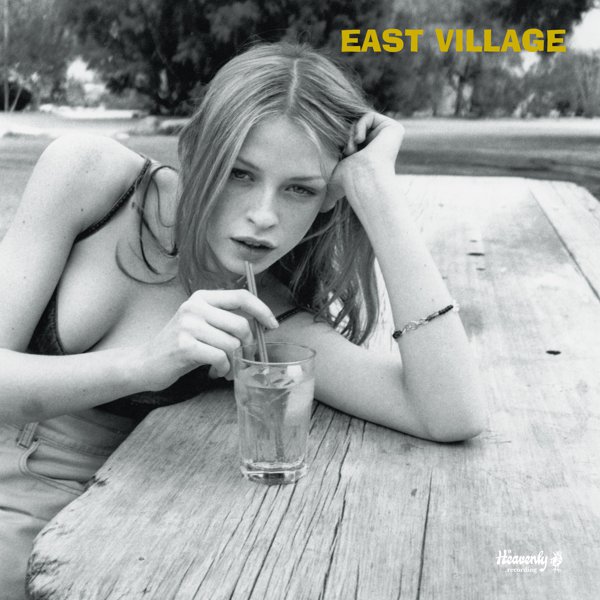

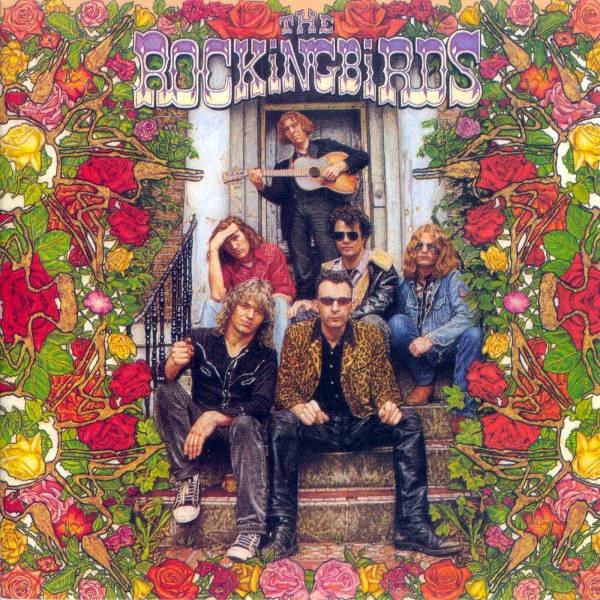

Unlike many independent record labels, you can’t really pin London-based Heavenly Records to any genre or scene. Founded by former Creation Records employee Jeff Barrett as the hedonistic freedoms of acid house bled into the 90s, early Heavenly releases on the one hand included Andrew Weatherall-produced seven-inch The World According To Sly & Lovechild (recently enjoying a new lease of life thanks to remix from Peggy Gou) and Flowered Up’s era-defining 16-minute single “Weekender,” and on the other, country rock revivalists The Rockingbirds and the debut singles from Welsh iconoclasts Manic Street Preachers. Indeed, even a label as quixotic as Creation might not have given an official catalogue number to a piece of artwork made from the wrapper of a cheese toastie purchased by Primal Scream’s Bobby Gillespie (HVN13 Toasted Cheese Sandwich by Paul Cannell).

If anything, over the past three decades Heavenly has been defined more by its spirit, something driven in no small part by the enthusiasm and passions of Barrett. Born in Nottingham, despite not having a passport or being able to drive, a young Barrett went from working in HMV to tour managing The Jesus And Mary Chain before taking on the loose job of “doing everything” for Creation, chiefly press and radio promotion. He set up his own press office Capersville out of Creation’s HQ and worked both Creation and Factory bands, including Happy Mondays for the latter. It was while trying to get press for Primal Scream’s largely unlovable second album that he had the idea of getting a new DJ/writer friend of his by the name of Andrew Weatherall to review the band, thus setting off a collaborative chain of events that resulted in the group’s game-changing third LP, Screamadelica.

Prior to starting Heavenly Barrett had run two small independents, Sub Aqua and Head, but it was the Weatherall connection which helped launch Heavenly with 1990’s The World According To Sly & Lovechild (HVN1). Though the record’s acid throb was on the bleeding edge of the contemporary club scene, Barrett never considered limiting Heavenly’s horizons to just being a dance imprint and as such over its thirty plus year history, releases have roved across styles and genres, led mainly by Barrett’s magpie tastes and reliably good ears.

“That is just a straight up reflection of what I, and anybody else that has been significantly involved in the label, am about. Me, the others, we just dig music and have the utmost respect for those that write it and play it,” says Barrett. “Well, the good stuff anyway.”

Beyond putting out records, Heavenly have diverged into putting on now legendary 90s club night The Sunday Social, which launched the career of The Chemical Brothers; Heavenly Films, responsible for award-winning documentaries on Felt/Denim/Go-Kart Mozart’s enigmatic leader Lawrence, Dexys Midnight Runners and others; a literary wing Caught By The River, which publishes books and puts on events focused on Barrett’s other great love, nature; and iconic central London bar and venue The Social.

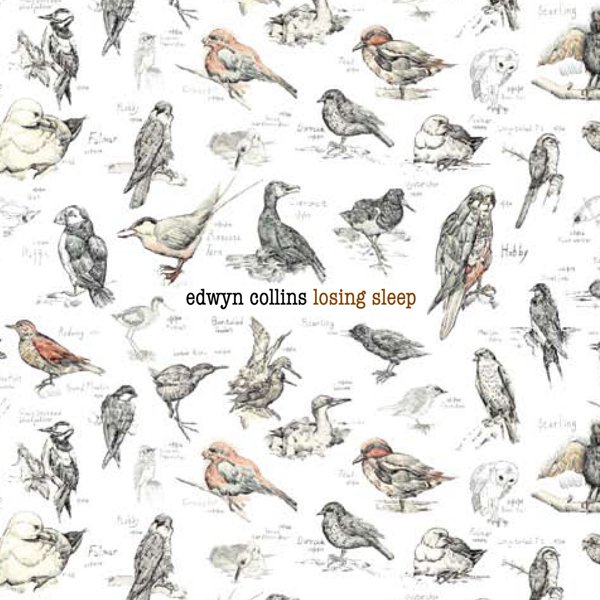

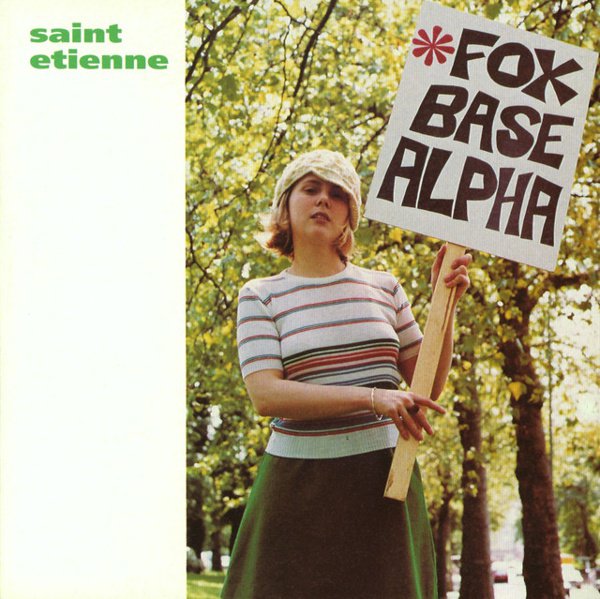

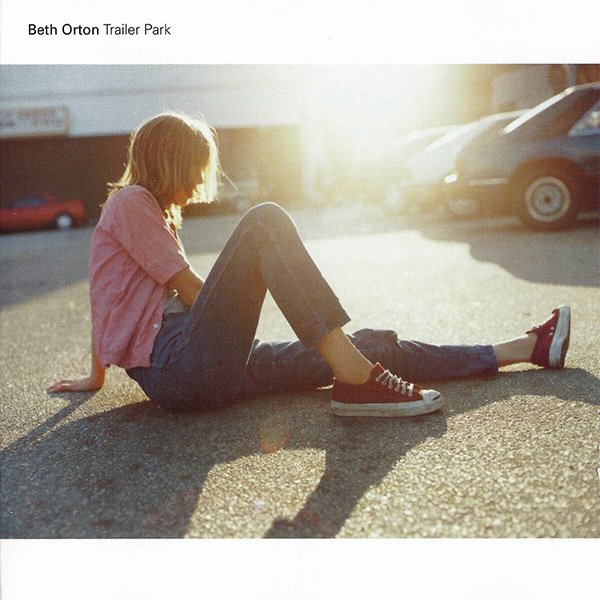

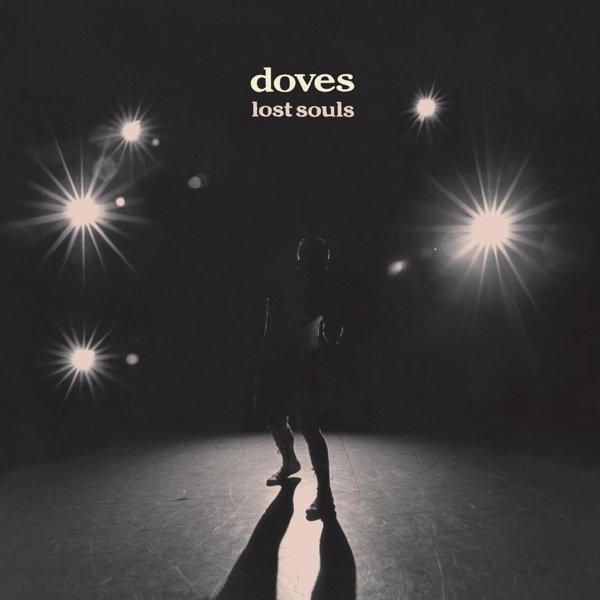

At Heavenly’s heart though is still the eclectic spread of great music the label has championed and put out over the years: albums from Saint Etienne, Beth Orton, Doves, the late Mark Lanegan, and more recently acts like Confidence Man, Baxter Dury, Australian psych rockers King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard and Yorkshire’s Working Men’s Club. Here’s a select bill of fare for some of Heavenly’s key releases…