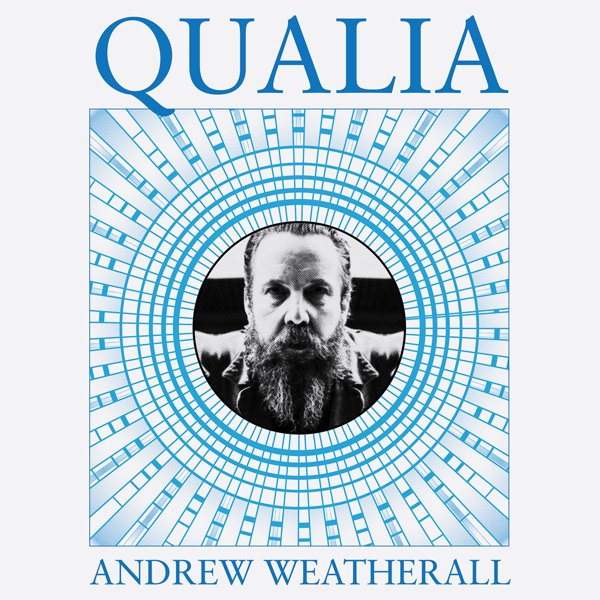

Trying to home in on the best of Andrew Weatherall’s work is a sanity-testing project. This is a man whose contributions to music were spread across many hundreds of hours of solo and collaborative releases, remixes and production work, and many thousands more hours of wildly diverse DJ sets – and beyond that there was also creative writing, journalism, anecdotes, visual art, styling, archival efforts, curation and more. And none of these were merely side projects, they were all knitted into his process, into the culture that Weatherall inhabited and created around himself.

As his friend of 30+ years, David Holmes, put it: “music was just something Andrew did, albeit brilliantly, but ultimately he transcended that.” Or to put it another way, Weatherall’s commitment to the culture was so absolute that everything he did, down to random phrase-making and the way he dressed, was a contribution to it. In one sense, each thing was an addition to a fantastically complex, multidimensional gesamtkunstwerk, in another it was just the output of someone who once described the common thread connecting his work as being the fact that “I really, really like making things.”

He was making those things long before he became the DJ / producer he’s best known as. Contemporaries from Windsor – the commuter belt town to the West of London he grew up in – fondly remember LSD-fuelled post-pub sessions in the early 1980s, where Weatherall’s collection of Krautrock, postpunk, roots and dub, northern soul, disco and more was the soundtrack. Then in 1986, his friendship circle formalised itself around the Boys’ Own brand with a party and a fanzine, which pulled together the mischievous banter of football terraces and soul weekenders with a musical evangelism spanning everything from Trouble Funk to Big Audio Dynamite, the Pogues to Psychic TV.

As voracious, switched on hedonists, Boys’ Own were perfectly placed to receive and redistribute the Balearic and acid house sacraments, and became a crucial nexus in the establishment of modern dance culture in the UK. With ecstasy added, their parties became the stuff of legend, and playing at them and at foundational clubs like Trip and Shoom, Weatherall established a reputation for not just being able to string together unlikely or incongruous tunes but to blend them into something greater than the sum of their parts. He also got his first taste of the studio – ripping up genre and technique rulebooks and reworking the likes of Happy Mondays and Primal Scream’s tracks into lasting club classics.

Working initially with studio engineer Hugo Nicholson, Weatherall launched into a golden period in the first couple of years of the 1990s. Remixes for the likes of Jah Wobble’s Invaders Of The Heart, James, Finitribe, My Bloody Valentine, Saint Etienne, The Grid, The Orb, One Dove and of course Primal Scream poured out, each time mixing new configurations of breakbeats, dub basslines, slowed down house hypnosis and more often than not signature ringing timbales. This period crested with the release of Primal Scream’s Screamadelica in late ‘91, about two-thirds Weatherall / Nicholson produced – and probably still the highest profile release associated with Weatherall’s name.

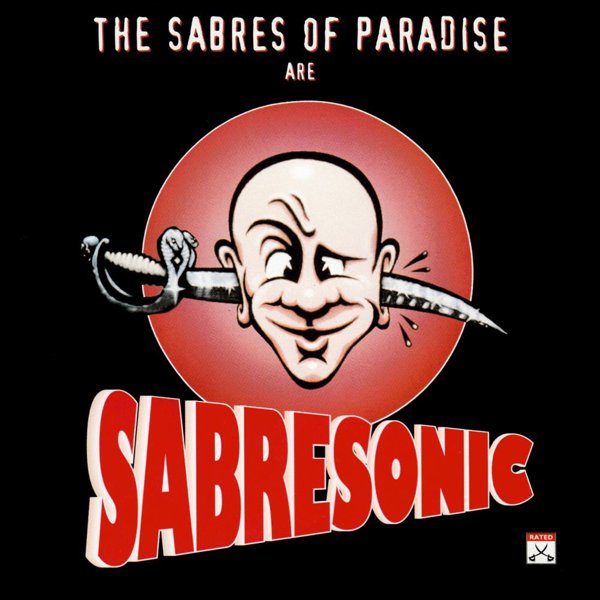

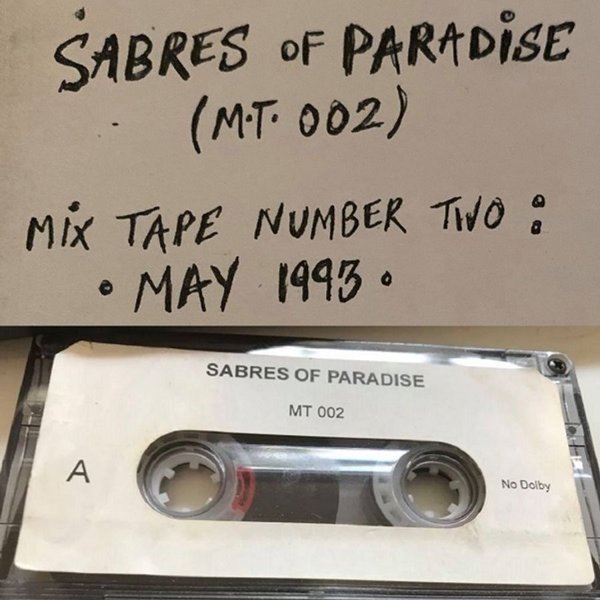

At the same time, he was rocketing into the international DJ big league, playing anything from hands-in-the-air Italo-house to deep dub – and post-Screamadelica Weatherall was as in demand as just about any remixer in the world. In 1992, however, he executed the first of the major sharp left turns that would initially get him a reputation for obstreperousness, but would ultimately prove to be core to his creative longevity. Along with new studio partners Jagz Kooner and Gary Burns, calling themselves Sabres Of Paradise – with a label of the same name and a club night dubbed Sabresonic – he moved away from Balearic optimism and towards minimalism, moodiness and an increasing love of techno and proto-trance.

Even with this darkness and experimentalism, his profile continued to skyrocket: had he continued brand-building, Weatherall could have very easily have become a global megastar DJ on a par with Richie Hawtin, Laurent Garnier or Carl Cox. But again, he swerved away from the spotlight. Sabres the band released two albums, one remix collection and untold remixes, but by ‘95 Weatherall was moving on, going deeper still sonically and moving towards the shifting mesh of creative partnerships that would define his work thereafter. He tested the waters with Lords of Afford with David Hedger, Bloodsugar with On-U Sound keyboardist and musical Zelig David Harrow, and most lastingly, Two Lone Swordsmen with Keith Tenniswood.

And the clubs and collectives multiplied too. As techno became harder and brasher in the late 90s, the Bloodsugar night pulled in the opposite direction, diving into lower, slower, more meditative depths that saw it pre-empting the “minimal” explosion of the 00s by half a decade. Haywire Sessions provided a platform for Two Lone Swordsmen and allies’ collisions of electro with UK dub soundsystem bass and spatial manipulation. The Double Gone Chapel saw Weatherall playing raw old rockabilly singles. First the Emissions family of labels and then the Rotters Golf Club stable put out work by his aliases, collaborations and strange friends. Each time these things were rooted in very specific times, places, social milieus.

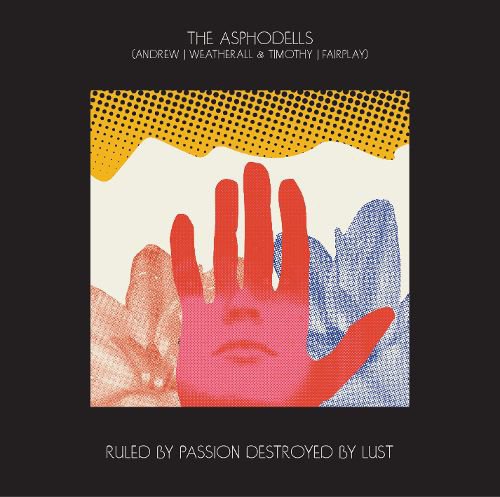

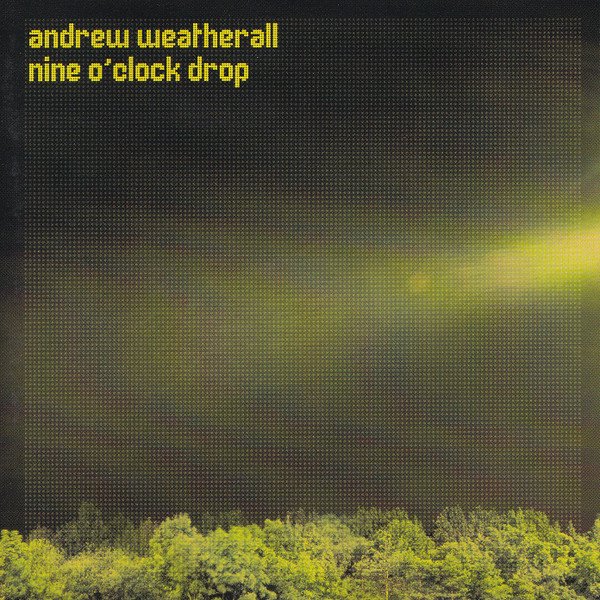

And on it went. After the 2004 Two Lone Swordsmen album From the Double Gone Chapel Weatherall would increasingly incorporate his own unadorned, untrained vocals and grittily poetic writing – informed by The Fall, Nick Cave and many generations of outsider rock. This would become a running thread through both solo records and those as The Asphodells with Timothy J Fairplay. In the 2000s, his abiding love of post-punk and proto-techno allowed him to casually smash out punk electronics alongside the best of the electroclash and nu rave generations. The various strands that had always been there in various phases or individual tracks – dub, breakbeat, goth, rockabilly, house and so on – now flowed into and out of one another as constants, combining and recombining in ever new hybrids.

People were constants too. In the 2010s, for example, a reconnection with Nina Walsh – formerly Weatherall’s romantic and business partner in the Sabres days – resulted in Walsh’s becoming his studio engineer for band production work, co-producer as Woodleigh Research Facility, and co-convener of the Moine Dubh label and event series, which incorporated folk, poetry and an emphasis on hand-produced artefacts into its ethos. Another reconnection with Sean Johnston, who had recorded for the Sabres label in the 90s, led to the A Love From Outer Space club and DJ partnership beginning in 2010, which defined a steady stepping sub-122bpm cosmic dance sound and nighttime ritual around which a passionate family of clubbers gathered, and which Johnston continues today.

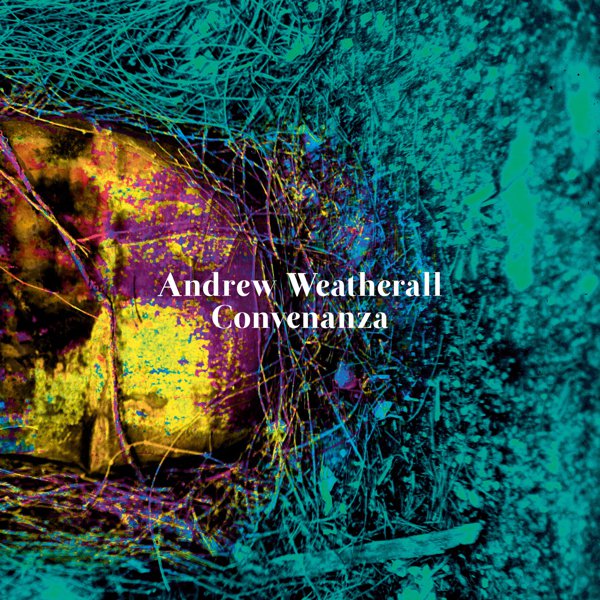

And there’s more. There’s always more with Weatherall. The Music’s Not For Everyone NTS radio show where he could play anything from scratchy old gospel to galactic scale synth jams. More or less straightforward production work for the likes of Fuck Buttons, Friendly Fires and Warpaint that created 21st century alt classics. The Convenanza festival in Carcassonne, Southwest France, which Bernie Fabre set up with Weatherall to join all of these threads together, which still continues. The writing, the woodcuts, the looks, the presentation of mystical ideas (“gnostic sonics!”)… and what’s more, Weatherall was still in full flow right up to his death at the start of 2020, so the volume of work just kept on accumulating at a dizzying rate.

This guide can only ever be a small window into the vast world that Andrew Weatherall built and expanded throughout his lifetime. But hopefully it gives a hint of the interconnectivity of that world. It includes as many DJ mixes as studio works, because the two things were inseparable: the various flavours of sets he played and residencies he held as a DJ acted as crucibles for studio projects and vice versa. And there were plenty of sets and projects that bridged gaps between specific styles or eras too. The hypersocial nature of the world Weatherall operated in means that friends and fans have documented and archived a huge number of his sets – again rooting them in time and place – most notably on the “Weatherdrive” online archive and the affiliated Flightpath Estate community. Even in death, Weatherall contributes to various subcultures – and by investigating his work and following its golden threads into his influences, record collection, collaborators and wider musical world, the minute you engage, you are building and shoring them up too. There’s a lot of deep magic in the way that Weatherall worked, but turning just listening to his work into a creative act in itself might just be his greatest spell of all.

![Live at the Heavenly Sunday Social [4th Sept 1994] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/5636705700282368_v1_600.jpg)

![Music’s Not for Everyone [2nd January 2020] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/5752469967077376_v2_600.jpg)

![Essential Mix [13th November 1993] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/4665686281945088_v2_600.jpg)